After the Kirk Killing

Plus: South Park genius; AI vs. MAD; UN widely beloved! And more!

Save the date: Just another reminder that next Saturday, Sept 20, at 1 pm US Eastern Time, I’ll have a Zoom discussion with paid subscribers about future plans for the NonZero Newsletter—a discussion that will include an issue that became even more pressing this week: how to fight national polarization, international polarization, and the “psychology of tribalism” that underlies both. Joining me will be two (fairly) recent additions to the NZN team: Nikita Petrov and Danny Fenster. A link to the Zoom call is at the bottom of this newsletter.

On Wednesday, hours after Charlie Kirk was killed, conservative podcaster Konstantin Kisin tweeted: “Tonight feels like some sort of invisible line has been crossed that we didn't even know was there. The last time I felt like this was 9/11 when it was clear, without knowing the how and the what, that the world was about to change forever.”

It’s a natural comparison—especially given that Kirk was killed on 9/10—but I think it’s in some ways misleading. And I think highlighting some differences between the al Qaeda attacks 24 years ago and the Kirk assassination this week can help us think about where we go from here.

Whereas 9/11, as Kisin suggests, came more or less out of the blue, 9/10 was different: We did know—broadly speaking, at least—that the line we crossed on Wednesday was there, and that we were heading toward it. There’s long been a sense that political polarization in this country was intensifying, with more and more violent manifestation, and there has long been a corresponding sense of foreboding.

No, we didn’t know the details. We didn’t know that the next big threshold would be the assassination of a young, wildly popular conservative media star and movement builder (let alone one who, in defiance of the spirit of the times, routinely engaged critics in debate). It could have been the assassination of some other popular and influential conservative, or for that matter a popular and influential progressive.

Or it could have been a protest that turned violent on a scale without recent precedent, leading to the deaths of multiple protesters and counter-protesters and maybe police or federal troops. But it was pretty clear that at some point we were likely to cross into terra incognita via especially salient violence, because the momentum in that direction has been tangible.

And, since Trump’s inauguration in January, another thing has become increasingly clear: In the event that the threshold-crossing violence turned out to be blue-on-red rather than red-on-blue, Trump would likely use that as an excuse to push the authoritarian envelope further than he’s already pushed it.

The early signs are that he will. The day of the killing he said: “My Administration will find each and every one of those who contributed to this atrocity and to other political violence, including the organizations that fund it and support it, as well as those who go after our judges, law enforcement officials, and everyone else who brings order to our country.” Given Trump’s capacity for generalization, that could be a lot of people and organizations.

The next day, to his credit, Trump said that Kirk was “an advocate of nonviolence” and “that’s the way I’d like to see people respond.” But he also said, to his discredit, “We have radical left lunatics out there and we just have to beat the hell out of them.” Buckle up.

If you’ve paid much attention to the commentary on the Kirk assassination, you’ve probably already been reminded that America’s descent into deeper tribal antipathy has been assisted by technology—in particular, by the incendiary dynamics of social media. Unfortunately, understanding the role of technology doesn’t lead straightforwardly to a cure. No magical re-engineering of our infrastructure for discourse is visible on the horizon.

And, precisely because this infrastructure has played such a big role in creating the current class of “influencers” (in the broad sense of that term), there aren’t a lot of highly influential people who can be counted on to play a constructive role. I suspect that if the current direction of the country is to be turned around, a lot of the energy will have to come from people and groups that aren’t on many radar screens right now.

One hope is that a role could be played by new, self-consciously anti-tribal movements that take shape at the grassroots level. There have been attempts at this, but no transformative model has emerged. One thing we’ll be discussing on the Zoom call mentioned at the top of this newsletter is why that is, and whether there are promising models that haven’t been tried.

I know what Kisin means when he said that, after 9/11, he had a sense that “the world is about to change forever.” I had a bit of that feeling, too.

And the world did change. The US embarked on multiple military interventions in Muslim nations, and there was, over time, immense blowback. The blowback included “home grown” terrorism that got especially intense in the year before the 2016 election (with both the San Bernardino and Pulse Night Club mass shootings) and helped Donald Trump get elected president.

That train wouldn’t have been set in motion had America had better leadership in the aftermath of 9/11. This is a reminder that human agency can play a big role in human events; wisdom can change the course of history. But wisdom didn’t come from the top after 9/11, and it’s not likely to come from the top after 9/10. If pivotal agency is to materialize, it will probably have to emerge from the bottom up. The good news is that the current technological infrastructure for discourse is a place where, in principle, that kind of thing can happen.

—RW

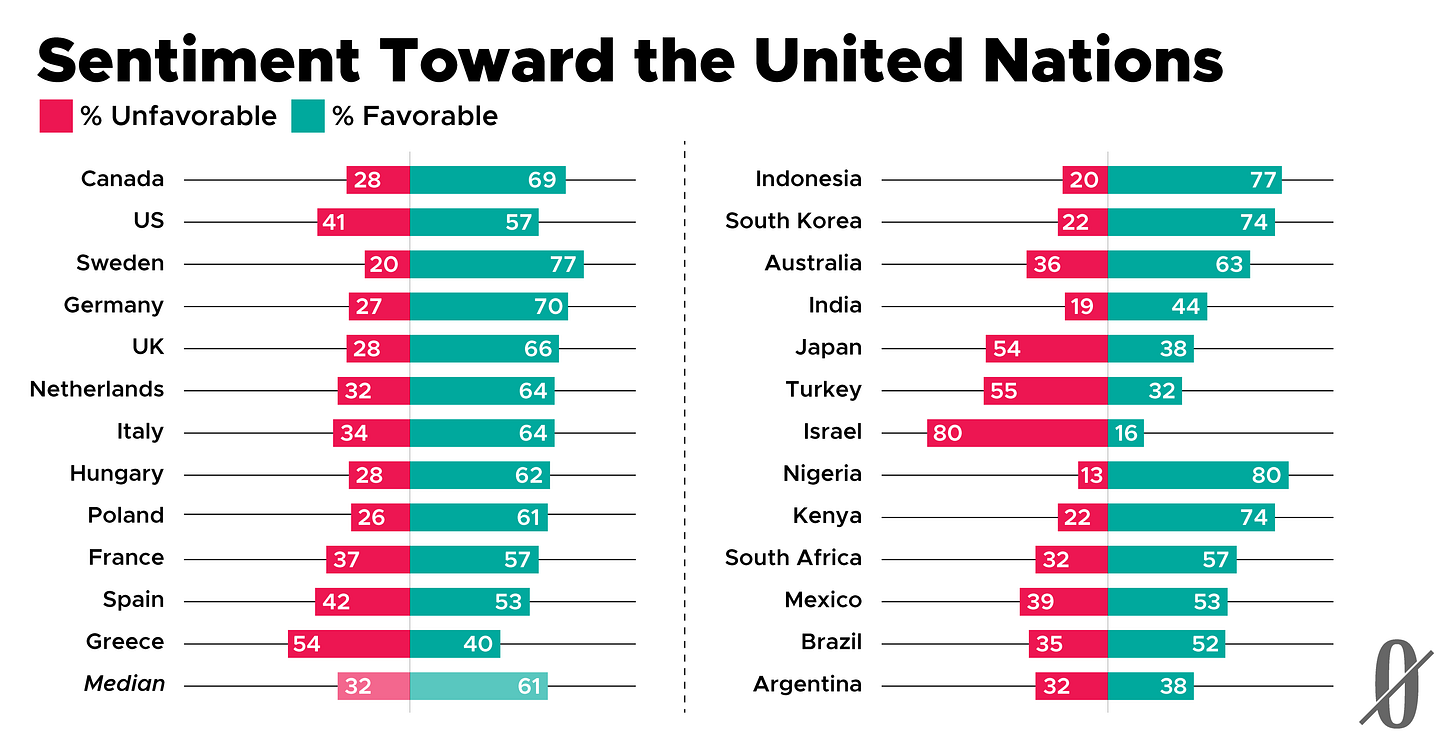

Lots of nations like the United Nations! That’s the upshot of a Pew poll conducted in 25 countries. Even in the US, whose current government is deeply hostile to the UN, most people have a favorable view of the institution. And as for the four countries that view the UN unfavorably—to understand the root causes of their attitudes, we’ve consulted some of the world’s most knowledgeable large language models. Their explanation is below.

Of the four countries with a net-unfavorable view of the UN, one is no surprise. It’s long been known that many Israelis believe, as Google’s Gemini put it, that the UN is “biased against Israel, as evidenced by a disproportionate number of critical resolutions and perceived lack of support for Israeli security.”

But what about Japan, Greece, and Turkey? ChatGPT, Claude, Gemini, and Grok turned out to be in general agreement on the main reasons for the hard feelings. They said that Japan, which has the fifth biggest economy in the world and has long been one of the biggest financial supporters of the UN, resents being denied a seat on the Security Council. And they said that Greeks and Turks tend to dislike the UN over the same thing: Cyprus, which has large populations of Greek speakers and of Turkish speakers. The northern third of the island nation has been occupied by Turkey since 1974—and, as Claude put it, the UN has made the "Greeks furious it won't uphold its own resolutions calling for withdrawal, the Turks equally furious it won't abandon them."

Will the first superpower to achieve artificial superintelligence enjoy overwhelming military dominance, as some have suggested? Probably not, because even advanced AI is unlikely to wholly undermine the logic of nuclear deterrence, argue Sam Winter-Levy and Nikita Lalwani in Foreign Affairs. True, such AI might render much of an enemy’s infrastructure for nuclear retaliation vulnerable, but there would still be old-fashioned physical barriers, like command centers deep underground, and new countermeasures would be devised by opponents. So the chances of retaliation would remain high enough to make a first strike forbiddingly risky.

Still, perception matters. Fears of AI vulnerability could drive states to expand arsenals, delegate launch authority, or shorten decision times—steps that heighten the risks of accident or escalation. So, though winning the race to artificial superintelligence may not bring global dominance, winning that race—or even having the race—could bring global annihilation.

If you’d like to hear more about how AI could prove catastrophic—or could be kept from proving catastrophic—check out my just-posted conversation with Holly Elmore, executive director of PauseAI US, available on YouTube or on the NonZero podcast feed.

Until this year I had never watched an entire episode of South Park. But the first two episodes of this season (the 27th!) got so much attention for their anti-Trump audacity that I had to take a look. And I was impressed. But the third episode—which was more about Silicon Valley than about Trump—impressed me even more, because it offers an ingenious grand unified theory of Venture Capital culture and AI psychology.

I elaborated on this in my podcast conversation with Nikita Petrov this week. If you didn’t have time to watch or listen, here’s the boiled down, social-media-sized version of my South Park exegesis:

President Trump has once again unified the nation—and, once again, the nation he’s unified isn’t the United States. Delays in the repatriation of hundreds of South Korean workers who were arrested in an immigration raid at a Hyundai–LG battery plant in Georgia fueled anger in Seoul, the NYT reports. Images of the detainees in handcuffs and ankle chains sparked ire across the political spectrum.

Lee Eun-ju, a prominent member of the left-of-center governing party, suggested that South Korea could suspend investments in the US or withdraw workers. The conservative newspaper Chosun Ilbo echoed the outrage, calling the raid “ruthless” and “unacceptable,” and warning that it “severely undermined trust in South Korea’s efforts to contribute to the US economy.”

Banners, images, and graphics by Clark McGillis.