How Bibi Boosts Antisemitism

Plus: Elon's sleuth fail; Eric Schmidt's China envy; drugged out LLMs; and more!

Israeli Prime Minister Bibi Netanyahu and staunchly pro-Israel New York Times columnist Bret Stephens agree on the cause of last week’s massacre of Australian Jews by ISIS-branded terrorists: the Gaza War.

Granted, that’s not exactly how Netanyahu and Stephens put it. In fact, that’s not how they’d ever put it. But there’s a sense in which the Gaza War is implicated by their explanations for the massacre. Understanding that sense can advance the conversation about the relationship between Israeli policy and antisemitism—or, at least, could advance that conversation if such a conversation existed. But it doesn’t; the question of whether Israel does things that endanger Jews around the world is a question mainstream US opinion-shapers assiduously avoid. I think continuing to avoid it could make Jews more endangered.

Netanyahu blamed the Australia attack partly on the Australian government’s decision to recognize a Palestinian state three months earlier. He said he’d warned Australia’s prime minister that this move would pour “fuel on the antisemitic fire.” But the Australian government ignored the warning and, more generally, failed to take measures to fight antisemitism, said Netanyahu; and “the result is the horrific attacks on Jews we saw.”

Stephens, for his part, wrote that “it’s reasonable to surmise that what [the killers] thought they were doing was ‘globalizing the intifada.’ That is, they were taking to heart slogans like ‘resistance is justified’ and ‘by any means necessary,’ which have become ubiquitous at anti-Israel rallies the world over.”

It’s true that those slogans have gotten a lot of air time over the past couple of years, in part because the number and size of those rallies grew. But of course, that was largely a response to the Gaza War. (I’d never heard the phrase “globalize the intifada” until one of my daughters, having attended a pro-ceasefire rally in late 2023, told me that some protesters were starting to chant it.) So if Stephens is right in thinking that the spread of such slogans has made violent forms of antisemitism more likely, then the Gaza War has made violent forms of antisemitism more likely.

Similarly, had the Gaza War never happened—or even if it had ended after six months—it’s unlikely that Australia would have wound up recognizing a Palestinian state in September of this year. So if Netanyahu is right that this recognition made the Australia attack more likely, then so did his decision to keep bombing Gaza long after Israel’s security could plausibly be said to require that.

Before I go any further, two disclaimers: (1) I have no idea what motivated those two Australian killers; they may well have been radicalized before the Gaza War, and whether the war in any sense helped push them over the edge is anybody’s guess; (2) even if I asserted that they were motivated by the war, and in particular by Israel’s sustaining the war for so long, I wouldn’t necessarily be saying that Israel is “to blame” for the killings. I’d be talking about the causal forces that contributed to this burst of violent anti-Semitism. I’m a big believer in insulating this kind of causal analysis from discussions of blame, even if those discussions will be informed by the results of the analysis.

In a way, it’s misleading for me to say Netanyahu and Stephens would never explicitly invoke the Gaza War in explaining antisemitic acts. They’re well aware that there’s been more antisemitic violence in the two years since the war started than in the two years before, and they don’t think this is a coincidence. But the way they signal this awareness is by talking about an upsurge in antisemitism “after October 7” of 2023, the day Hamas started the war by attacking Israel. They talk as if the world’s antisemites had been waiting for a signal from Hamas before swinging into action, and nothing Israel did in the ensuing weeks and months mattered.

Stephens, for example, writes that “in the wake of Hamas’s attack of Oct. 7, 2023, the [Australian] legislator Jenny Leong went on a rant accusing ‘the tentacles’ of the ‘Jewish lobby and the Zionist lobby’ of ‘infiltrating into every single aspect of what is ethnic community groups.’ ” Leong said this on December 13 of 2023—which, yes, is in the “aftermath” of October 7, but is also a date by which Israel had killed more than 18,000 Palestinians, at least half of them civilians, in response to an attack that had killed 1,200 Israelis. That doesn’t justify what she said, but it suggests that “October 7” per se may not have been what got her so worked up that she said it. And it suggests that policy decisions made by the Israeli government may have some influence on the amount of antisemitism in the world, or at least on the extent and form of its expression.

Leong’s phrase “the Jewish lobby and the Zionist lobby” is significant. The conflation of Jews and Zionists—and the related conflation of global Jewry and Israel—is a famously common feature of antisemitism, a feature that facilitates the psychological transmutation of revulsion at Israeli policies into hatred of Jews. This conflation is also famously confused. After all, (1) not all Jews are Zionists and not all Zionists are Jews; and (2) most of the world’s Jews don’t live in Israel.

It seems like a good idea, if you want to minimize the exposure of the world’s Jews to antisemitic attacks, to do things that discourage this confused conflation. But that has not been Bibi’s approach.

Netanyahu is prime minister of Israel, not king of the Jews, yet he has stood before the UN General Assembly and said he was speaking “on behalf of my people, the Jewish people.” He has also stood before the US Congress and said “I speak on behalf of the Jewish people.” And he has tweeted, in advance of a speech before Congress, that he would be speaking as an “emissary” of “the entire Jewish people.”

When Netanyahu visited Paris in the wake of the 2015 antisemitic attacks there, and then said he’d gone as “a representative of the entire Jewish people,” one of these Jewish people, Sen. Diane Feinstein, called his attitude arrogant. For that matter, his attitude doesn’t seem to have won unanimous acclaim from Parisian Jews. He said to a gathering of them, “To all the Jews of France, all the Jews of Europe, I would like to say that Israel is not just the place in whose direction you pray, the state of Israel is your home”—and they responded by spontaneously singing the French national anthem. Maybe they were trying to remind him that the “dual loyalty” trope has a history of antisemitic deployment.

In a way you can’t blame Bibi. An important part of his job—seeking support for Israel from powerful nations, especially the US—pretty much dictates that he try to strike chords of affinity among their Jewish populations. And this encourages him to do various things that may blur the line between Israel and world Jewry. Like, for example, tirelessly referring to Israel as “the Jewish state”—a formulation that’s technically accurate but will still have that blurring effect in some minds.

Still, even if you can’t ask the leader of Israel to work 24/7 to fight the Jewry/Zionism/Israel conflations, you can ask two things: 1) that the leader of Israel work harder at that than Netanyahu has worked; 2) that the leader of Israel accept the implications of the fact that, largely because of this enduring conflation, the policies of Israel can have an impact on the safety of the world’s Jews.

For example: In May of this year a man in Washington, DC, killed two Jews, one American and one Israeli. There’s no way to know for sure that they’d still be alive if Netanyahu had quit bombing Gaza, say, a year earlier—after seven months of war and 35,000 dead Palestinians. But, given that the killer yelled, “I did it for Gaza,” there’s a pretty good chance.

The link between Israeli policy and antisemitism would matter less if the Gaza War was truly over and was going to be the last major episode of violence involving Israel for a while. But there’s no end to the violence in sight. The October 7 attack strengthened a longstanding strain of thought in Israel about its national security: that Israelis will always be hated by most of their neighbors, so the only viable strategy is to keep those neighbors too weak to overwhelm Israel. That means recurring military strikes on Lebanon, Syria, Iran, and maybe other nearby nations.

Not to mention the Palestinians, whose suffering in Gaza has distracted the world from their ongoing incremental displacement in the West Bank, often via violence. The complete ethnic cleansing of both the West Bank and Gaza has more popular support in Israel now than before October 7 and, I’d guess, significantly more than public opinion polls would reveal.

All told, then, Israel seems more committed than ever to a strategy that is likely to sustain if not increase the incidence of violent antisemitic attacks beyond its borders, including in the United States and Europe. And to the extent that mainstream American and European commentators remain reluctant to talk about the connection between this strategy and these attacks, the strategy will be that much more likely to persist.

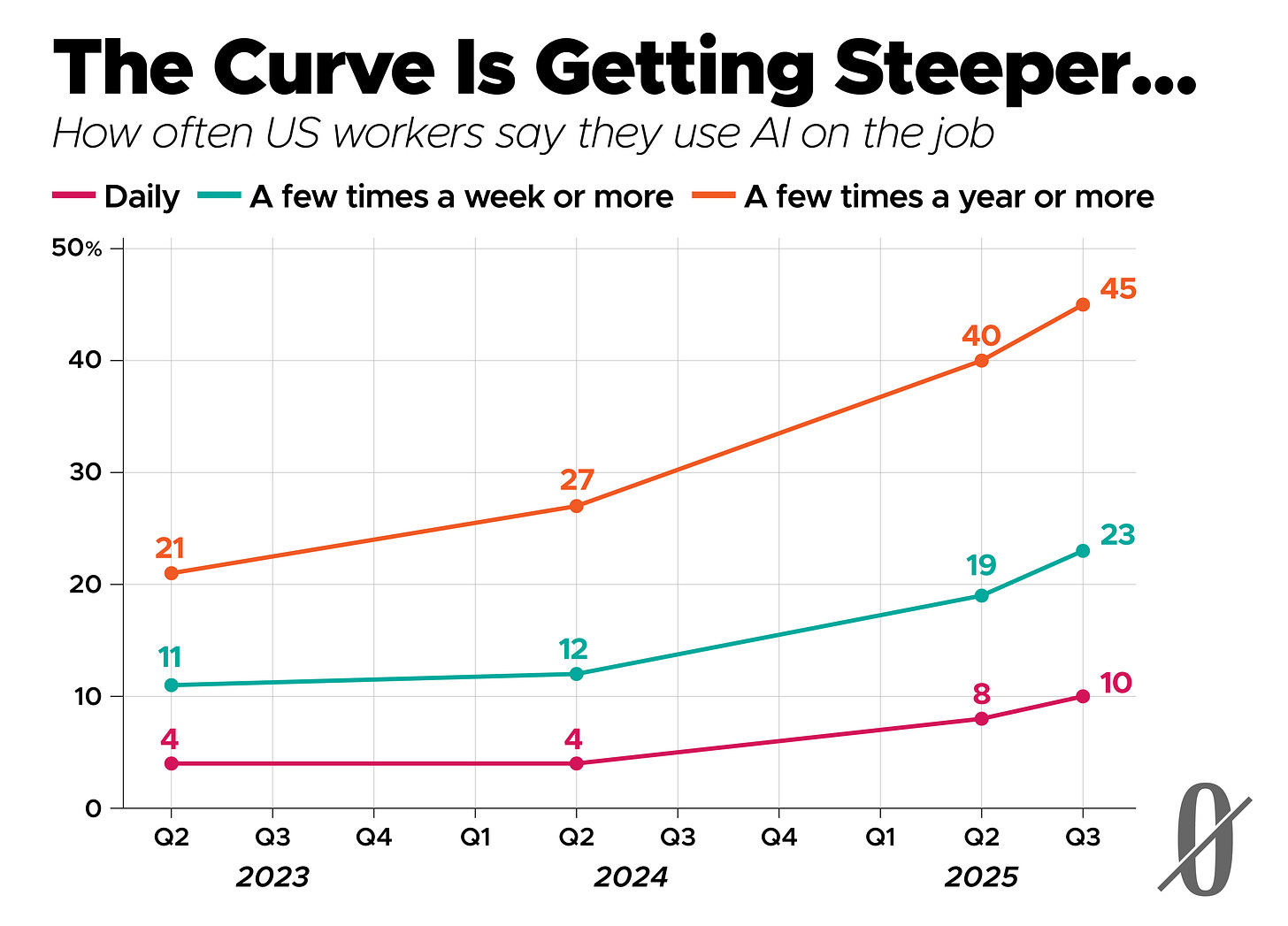

The above graph, like a lot of other data, suggests that artificial intelligence is insinuating itself in American life at a pretty brisk pace.

But not brisk enough for some people! A few months ago former Google CEO Eric Schmidt co-authored a New York Times op-ed in which he chastised Silicon Valley for failing to generate a “Cambrian explosion of imaginative, unexpected uses of AI.” He noted with alarm that “a recent working paper by the National Bureau of Economic Research showed that most people in the United States still use generative AI infrequently.” That paper, it turns out, is titled “The Rapid Adoption of Generative AI”—but I guess you don’t get to be as rich as Eric Schmidt in the course of a single human lifetime by settling for “rapid.”

Schmidt has some ideas about how to address the grave problem of technological stagnation in America. He writes, for example: “Why are there no competitions among American farmers to use AI tools to improve their harvests?”

It feels weird to explain this to a titan emeritus of Silicon Valley Big Tech and a highly successful venture capitalist, but: There already is competition among American farmers to use AI tools to improve their harvests. It’s called the free market!

What is Schmidt trying to do—turn American capitalism into statist capitalism, like China’s? Maybe so. It turns out that he got his farmer faceoff idea from rural villages in China, where, he notes, “competitions among Chinese farmers have been held to improve AI tools for harvest.” And he reports admiringly that “last year China started the AI+ initiative, which aims to embed AI across sectors to raise productivity.” Indeed, the main impetus behind Schmidt’s whole jeremiad is his belief that “our nation risks falling behind China.”

One advantage Schmidt thinks China has over the US is techno-optimism. One poll, he says, found “that only 32 percent of Americans say they trust AI, compared with 72 percent in China.”

But maybe that reflects a problem that Schmidt’s proposals don’t address. Maybe Americans see that the US government has so far shown little inclination to regulate AI and so can’t be counted on to insulate them from its bad effects. And so long as Silicon Valley potentates seem to encourage government intervention only to speed things up, and never to slow things down, maybe that perception won’t change.

It’s high time that somebody put the “high” in “high tech.” And somebody has. As Wired reports, a Swede named Petter Ruddwall has opened Pharmaicy, an online shop featuring “code-based drugs” that make ChatGPT act intoxicated—with cannabis, ketamine, cocaine, ayahuasca, and alcohol among the options. People on paid ChatGPT tiers can upload files that get their bot to mimic a human in various altered states—a “hazy, drifting” vibe for cannabis, dissociation for ketamine, etc. In one trial, a Stockholm educator dosed her chatbot with an ayahuasca module for brainstorming purposes and said she got unusually “free-thinking” feedback.

Ruddwall refers to his process as a way “to unlock your AI’s creative mind.” But others, like Google researcher Andrew Smart, hesitate to use that kind of language, insisting these code modules are “just messing with outputs.” Well, maybe. But isn’t that what a drug experience always looks like when you’re observing it from the outside?

This week brought some news you can use: Next time you’re trying to crack a murder case, don’t call on the services of Elon Musk. And you might avoid Israeli intelligence officials as well.

Musk had lent his credibility to the theory that the Brown University shooter was a lefty whose target was the vice president of the student Republican Club, one of two students who died in the attack. Meanwhile, Israeli sleuths thought they had a lead on a different murder—the shooting of an MIT nuclear physicist in his apartment. The Jerusalem Post reported that “Israeli officials are examining intelligence from recent days that suggests an Iranian connection to the murder of Prof. Nuno Loureiro.”

It turned out that the two shootings were the work of the same person, and his motivation had nothing to do with Iran or with Republicans. He was a middle-aged man whose plans to be a great physicist had come to naught. The victims of the Brown shooting had the misfortune of being in a building where he’d taken physics courses while a graduate student. And the MIT physicist had been his classmate as an undergraduate in Portugal.

We shouldn’t be too hard on this week’s failed detectives. Israel has assassinated a lot of Iranian nuclear physicists, so it wasn’t entirely crazy to think that Iran might eventually retaliate in some fashion. And as for Musk’s theory: Well, these are polarized times, so you never know. Still, both Musk and the Israeli officials were illustrating a tendency that helps sustain polarization, both international and intranational: tribal threat inflation—thinking that the enemy tribe is more menacing than it actually is.

Banners and graphics by Clark McGillis.

Many good points.

It seems to me that the public space is only interested in causality in the sense of blame. When earlier in the day, after a horrific murder/rape, the police would issue advice for women to avoid certain areas for their safety, they were criticises for shifting the blame onto the victims, when they were doing no such thing. When US-critical commentators following 9/11 said that if the US played a more positive role in the Middle East and was not seen as an agent of opression, suffering and death, the terrorists would've had no grievances against it, they were likewise vilified. And the same here. Of course, tribalism is the elephant in the room, conflating Israelis, Jews and Zionists is just a crude by-product of tribalism, IMO. Lumping people together. As if those Jews on Bondi Beach were implicated in the atrocities by virtue of being Jews. Another element is plentiful media showing carnage and heart-rendering scenes, agents of radicalisation and as distasteful as it may be to say it, it is no surprise that Bondi Beach massacre happened. Sadly, it is surely one of many to come, as much as the security services will probably prevent most of them.

Given the crises we are faced with, it is encumbrant on us all to start seeing ourselves as Earthlings, first and foremost, and members of whatever ethnic and religious identity, second. But again, the current developments appears to be pointing in the opposite direction.

(A footnote: Jews can be as tribal as anyone else, and internalise praise and blame for acts by other Jews and indeed, the State of Israel. Our history and tradition/religion indeed make this tendency quite likely. The Judaic myth of being chosen by God, the Exodus from Egypt at the expense of innocents of other peoples, etc. Sure, Jews process these stories in a variety of ways, ranging from humourous dismissal to a sense of heightened responibility, but they do leave a mark, like a stigma against intermarriage. A history of persecution makes people stick together for survival. Even genetically most Jews (Ashkenazim) descend from roughly 1000 individuals in Europe of about 1000 years ago, a roughly 50-50 Levantine and South European mix, so Jews are remarkably genetically similar.)

What is the meaning of anti-Semitism, anyway? Why are the killings on Bondi Beach "anti-Semitic"? Who says they are? Is it because the crimes were committed against members of the Jewish communuity? Does that mean that any crime against any Jew is anti-Semitic? Does that make any sense at all? The fact is the term anti-Semitism has been so weaponized and generalized that it is impossible to say who is and who is not anti-Semitic, as Jeremy Corbyn found out the hard way. People who cleverly manage to define anti-Semitism as being any person who disagrees with them are in possession of a magic weapon. The worst response to the accusation of anti-Semitism is to deny it. Denial leads to grovelling which leads to being crushed. If the Gaza genocide has accomplished one thing it is to expose the maliciousnees of the term anti-Semitism. Like Nicki Haley, Americans are increasingly supportive of efforts to "finish the job", only they will have a different interpreation than what she apparently intended.