Is Marc Andreessen just flat-out dumb?

Plus: Shy China; War on poverty stalls; Anthropic's sketchy cyberattack claim.

Washington’s policy toward AI is currently in the hands of accelerationists—people who believe faster technological progress is just about always better, so government regulation is just about always bad. That’s why President Trump, having already shut down the minimal federal AI regulation installed by his predecessor, is now considering an executive order that would punish states that pass their own AI regulations. Trump’s billionaire Silicon Valley backers want this done, so Trump may well do it.

Given the stakes—given the many fronts along which AI will bring abrupt and possibly destabilizing change, and the various dystopian AI futures that various analysts see—it’s worth asking: Do these accelerationists deserve our trust? Are they smart people with sound judgment? Are they intellectually honest?

Let’s take a look.

An excellent candidate for paradigmatic tech accelerationist is Marc Andreessen. He is co-founder of the powerhouse Silicon Valley venture capital firm Andreessen Horowitz, and I suppose he’s a “thought leader”—certainly he loves to express big thoughts publicly, and they tend to get attention. In addition to expressing them on the Andreessen Horowitz podcast (a16z), he periodically posts treatises with titles like “Why AI Will Save the World” and “Techno-Optimist Manifesto.”

In that second essay, Andreessen trotted out such maxims as “everything good is downstream of growth” and “Energy is life” and offered such suggestions as “We should raise everyone to the energy consumption level we have, then increase our energy 1,000x, then raise everyone else’s energy 1,000x as well.” Now, I don’t know about you, but I don’t see a mere 1,000x increase meeting my personal energy needs, so I breathed a sigh of relief when Andreessen went on to add: “We should place intelligence and energy in a positive feedback loop, and drive them both to infinity.”

If there’s one thing all accelerationists agree on (aside from accelerationism) it’s that boosting productivity is a good thing—boosting productivity in the economy as a whole and boosting their own personal productivity. Among Andreessen’s personal productivity boosters, it seems, is authoritatively dismissing concerns about technology without wasting precious seconds coming to understand those concerns in the first place.

Last year in NZN, I noted one example of this: Andreessen sweepingly dismissed past “panics” about the outsourcing of jobs by noting that “by late 2019… the world had more jobs at higher wages than ever in history.” Well that’s interesting, but since concerns about outsourcing are concerns about jobs moving from one nation to another, data about the total number of jobs in the world doesn’t speak super-directly to the issue at hand. Yet that number was the sum total of the evidence on which Andreessen based what he seemed to think was a devastating riposte.

Two weeks ago I noticed another example of Andreessen’s productivity-boosting deployment of incomprehension. Andreessen, a libertarian billionaire, was talking about AI during a podcast conversation with his libertarian billionaire VC partner (Ben Horowitz) and libertarian billionaire White House AI “czar” David Sacks, when he alluded to a concern that some non-billionaires have about AI: It could wind up concentrating power in the hands of a small number of people and institutions, at the expense of the masses. Will we, asked Andreessen, indeed see “one or a small number of companies or for that matter governments or super AIs that kind of own and control everything”—and, in the extreme case “you have total state control”?

That question, he said, has pretty much been answered: We’re discovering that “AI is actually hyperdemocratizing.” After all, he continued, AI has “something like 600 million users today, rapidly on the way to a billion, rapidly on the way to five billion.” (He was presumably thinking of ChatGPT, which according to OpenAI has more than 650 million weekly users.)

I’m trying to imagine Marc Andreessen, a few decades ago, discussing Orwell’s 1984 in an undergraduate seminar. Before the professor has a chance to launch the conversation, young Andreessen blurts out: “I thought this novel was supposed to be about a country where the people are controlled by the government and don’t have any rights. But it turns out that everybody gets free access to a TV screen!”

I admit that’s not a precisely apt analogy. Large language models allow us to learn more, do more, create more than we can learn and do and create with a TV screen. This kind of value is what Andreessen has in mind when he calls AI “hyperdemocratizing.”

It’s fine for Andreessen to emphasize this value, and it’s fine that he calls it “empowering,” which it in some sense is. But to think that this qualifies as a serious rebuttal to concerns about concentrations of AI power is to miss the point.

Those of us who have those concerns understand that people find AI valuable (including, yes, in ways that are “empowering”). Indeed it’s because of this value—because AI can serve as creative tool, educator, counselor, whatever—that so many people will spend so much time with AIs and become so dependent on them. And that in turn will make it possible for these AIs to become instruments of mass influence—to shape our political views, our shopping habits, our allegiances, whatever. That’s what will give the people who control the AI so much potential power.

These people could, for example, exclude journals of certain ideologies from a large language model’s training data. In fact, for all we know they’ve done that—but since people like Andreessen have carried the day in Washington so far, we have no way of knowing; there’s no law that compels the big AI companies to tell us what data their AIs trained on.

Or the influence could just be a byproduct of an AI company’s business model. Large language models might steer us toward products and services not just via recognizable advertisements, but by means so subtle that we’re oblivious to them. The persuasive powers of LLMs have been demonstrated in multiple studies, and those powers will grow—especially when the LLM you find so “empowering” has recorded everything you’ve ever said to it and in some ways knows you better than you know yourself.

I could go on listing examples of possible nefarious influence. But the general point is this: If there’s a machine that plays a growing role in guiding our lives, and is in some ways more clever than us, and has access to tons of information about us, the question of who’s controlling that machine, and what their agenda is, matters. So does the question of how many different people or companies or other institutions offer this technology, and what their relationship is to one another—in other words, the question of how much real choice we have about the kind of AI we use.

Whether concerns about AI-abetted concentrations of power are valid is an issue reasonable people can disagree on. What reasonable people can’t do is think they’ve demolished these concerns by noting that AI is proving valuable to people and therefore is enjoying widespread adoption. Widespread adoption is a pre-requisite for these concentrations of power—and pretty much everyone who’s concerned about the concentration-of-power problem already understands that the adoption will be driven by the value people see in AI.

So in noting that AI is “empowering” people and so is enjoying widespread adoption, Marc Andreessen has moved the ball zero yards. But, as usual, he’s too busy doing an end zone dance to notice that fact.

I don’t think Andreessen is dumb. And I doubt he’s consciously dishonest. But I do think Upton Sinclair was onto something when he said, “It is difficult to get a man to understand something when his salary depends upon his not understanding it.”

PS: Speaking of concerns about unhealthy concentrations of AI power: This week, in an episode of the NonZero podcast, I talked with Alex Komoroske, co-founder and CEO of the startup Common Tools. Alex is concerned about such concentrations of power and has some ideas about how to prevent them.

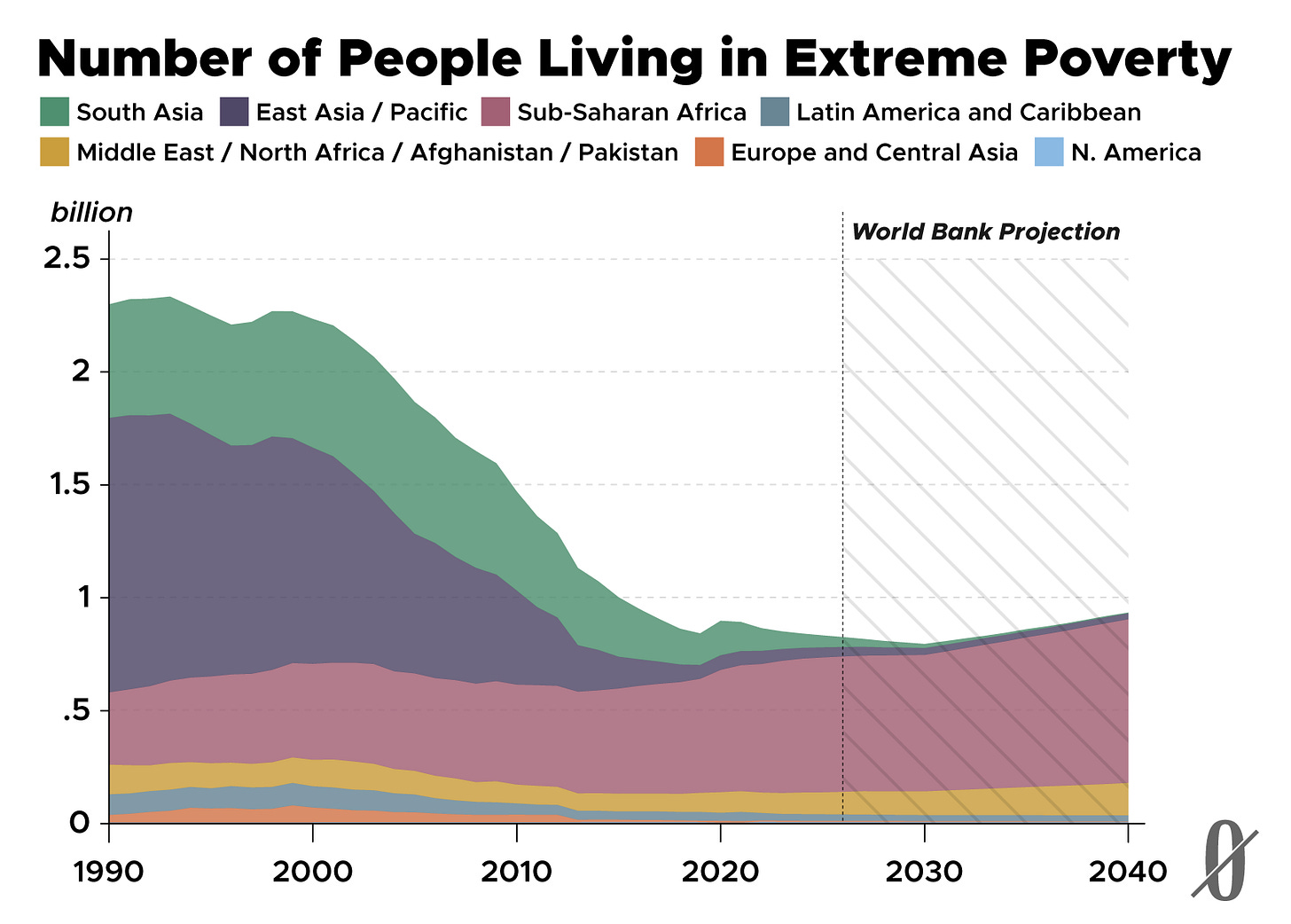

In Our World in Data, Max Roser argues that the sharp reduction in poverty seen in recent decades is unlikely to continue. The countries that have seen rapid declines in poverty by and large can’t continue to see them because the poverty rates have gotten so low. And for most countries with high poverty rates, there aren’t a lot of obvious causes for optimism. “Today, the majority of the world’s poorest people are living in economies that have not achieved economic growth in the recent past.”

In Foreign Affairs, political scientist Maria Repnikova argues that as the US reduces its deployment of “soft power”—dismantling USAID, shrinking the State Department, making visas scarcer—China is reluctant to fill the void. China, she writes, isn’t especially inclined to export its values and for now is “passively gaining stature” by, for example, being less meddlesome than America has traditionally been. “Unlike the Washington of the past, Beijing is more interested in legitimizing its distinctive path than in convincing others to follow in its footsteps.“

Anthropic recently said that—in what it called “the first reported AI-orchestrated cyber espionage campaign”—one of its Claude large language models was used to infiltrate dozens of organizations. In The Conversation, Toby Murray, a professor of cybersecurity, evaluates Anthropic’s report and says it “lacks the fine details that the best cyber incident investigation reports tend to include.” He might have added that such corroborating details would be especially welcome given that (a) Anthropic attributes the attack to Chinese state actors and (b) Anthropic’s CEO, Dario Amodei, is a strident China hawk, and Anthropic has cited the Chinese threat as reason for Washington to support big AI companies like, for example, Anthropic.

Now about that makeup session of the NonZero Reading Club: The reading will again be chapter five of Norbert Wiener’s 1964 book Gods & Golem, Inc, which is available here. But we’ll also be discussing the recent bestselling AI doomer manifesto If Anyone Builds It, Everyone Dies, by Eliezer Yudkowsky and Nate Soares. However, you shouldn’t feel you have to read the book to join in. I’ll be giving a short summary of it to launch that part of the discussion. (You might Google a review or two of it—and if you want to read a long and mostly sympathetic review, there’s Scott Alexander’s here.) Again, to join the discussion, just follow this link (trust me!) on Saturday, Dec 6, at 12 pm US Eastern Time.

Banners and graphics by Clark McGillis.

The chart on "Number of People Living in Extreme Poverty" is misleading: https://www.theguardian.com/global-development-professionals-network/2015/nov/01/global-poverty-is-worse-than-you-think-could-you-live-on-190-a-day

Andressson doing an endzone dance -- what an image