While you were impeaching your president…

Plus: Why Republicans doubt climate change; secular Buddhism; Elon Musk’s profundity, etc.

Welcome to NZN! In this issue I (1) recap a week that included lots of consequential non-impeachment news, ranging from Trump’s sabotaging of global governance to his threatening free speech on campus to some victories for Trumpism abroad to (lest you get despondent) some good news from outer space; (2) explore a study that may explain why climate-change skepticism has grown on the right even as evidence of global warming has accumulated; (3) share part of a conversation about “secular Buddhism” that I had with Stephen Batchelor, whose name is pretty much synonymous with that term; (4) steer you to background readings on things ranging from the virtues of modesty to Elon Musk’s profundity (seriously) to the reasons for America’s endless militarism.

The week in non-impeachment news

If you’re the kind of person who likes to watch movies even when you know how they’ll end, you may have spent much of the past week focused on impeachment proceedings (which—in case you’ve managed to avoid the plot spoilers so far—are sure to end in President Trump’s acquittal by the Senate, with his base having been energized in the meanwhile). Personally, I hate watching movies when I know how they’ll end—especially this one! So I’m well positioned to tell you what’s been going on in the world this week other than impeachment.

And a lot has been going on. Unfortunately, much of it, from the vantage point of my own ideology, has been bad. If you, too, find this summary of the week’s big events a bit dispiriting, just remember this. OK, here goes:

A kinder, gentler Trump: British Prime Minister Boris Johnson won re-election, as his Conservative party routed Jeremy Corbyn’s Labour Party. This apparently means that Brexit will happen next month, though the terms of the post-Brexit economic relationship between Britain and Europe won’t be worked out until long thereafter. Also, Britain may get smaller. The Conservatives lost big in mainly anti-Brexit Scotland, which may now seek a second referendum on whether to secede from the United Kingdom. And, for the first time, most members of parliament from Northern Ireland favor ditching the UK for union with Ireland.

A not much kinder, not much gentler Trump: Narendra Modi, the ethno-nationalist Prime Minister of India, hailed his parliament’s passage of a bill that would create a path to citizenship for migrants from nearby countries—with the notable exception of migrants who are Muslim.

New campus speech code: President Trump issued an executive order that allows the government to punish colleges for permitting the expression of certain kinds of criticism of Israel. The “Executive Order on Combating Anti-Semitism” adopts the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance’s definition of anti-Semitism, which deems anti-Semitic several kinds of extreme criticisms of Israel, such as calling the “existence of a state of Israel a racist endeavor” or “requiring of [Israel] a behavior not expected or demanded of any other democratic nation” or “drawing comparisons of contemporary Israeli policy to that of the Nazis.” So would colleges lose federal funding if, for example, they didn’t discipline a student who said during a panel discussion that Israeli soldiers use “Gestapo tactics” against West Bank Palestinians? I guess we’ll find out.

The order was welcomed by the Anti-Defamation League and some conservative Jewish groups but not by the ACLU or progressive Jewish groups. A number of Jews objected to the order’s implication that Jews are a national or racial, not just a religious, group. (The order grounds its authority in Title VI of the Civil Rights Act, and Title VI bars discrimination against national and racial groups but not religious groups.) As various commentators pointed out, the idea that Jews are a racial or national group has often been deployed by anti-Semites (in, for example, attributing to all Jews an allegiance to Israel).

Big brother: The Justice Department’s Inspector General said that the FBI’s investigation into Russian influence on the 2016 election was deeply deficient, particularly in its use of misleadingly selective information to secure wiretapping warrants. This in turn raised questions about the hundreds of wiretaps that are authorized each year via the secretive FISA courts (which virtually never deny a surveillance application from the government). The IG didn’t find that, as President Trump had claimed, the FBI lacked a sound basis to launch its investigation in the first place—but Attorney General William Barr still hopes to establish as much via a second investigation he has authorized.

Global governance sabotaged: Trump finally succeeded in paralyzing the World Trade Organization’s adjudicatory mechanism, which decides which countries have violated trade rules and authorizes punitive sanctions against them. Trump has been ritually blocking the appointment of new judges to the WTO’s appellate panel for years, and this week mandatory retirements reduced the number of judges left on the panel below the minimum of three. So any country that doesn’t like a ruling issued by a lower-level WTO panel can just file an appeal and put the case in a limbo that will last until…apparently until there’s a new US president.

Some people on the left approved of Trump’s hobbling of the WTO, noting that its adjudicatory process has sometimes deemed progressive national laws unfair impediments to trade. Which it indeed has. But I think in the long run the best way to serve progressive values amid rapidly globalizing capitalism is to have meaningful transnational governance—especially in the realms of labor and environmental regulation—and you can’t do that without strong bodies of global governance. Of course, this scenario assumes that transnational trade agreements are capable of evolving in a leftward direction. Well, as it happens, this week brought an example, or at least a partial example, of that:

NAFTA 2.0: Congress and the White House reached a deal that ensures passage of Trump’s renegotiated version of NAFTA. The new version isn’t radically different from the old NAFTA, and by progressive lights it has problems—notably a continued shortage of regulations dealing with climate change and other environmental issues. But it does have at least one interesting innovation: It requires that at least 40 percent of the content of cars that trade freely within North America be made by workers earning at least $16 an hour. The idea is that Mexican factories can either raise wages or watch jobs migrate north. Whether or not the $16 threshold is well calibrated, this is the kind of regulation that could soften the blow of globalization on American workers without resorting to unilateral trade barriers, which risk mutually destructive trade wars. So it’s important as a precedent, and as an example that bodies of global governance can, over time, evolve ideologically.

How the mighty have fallen: Aung San Suu Kyi, the prime minister of Myanmar who was once a hero of human rights activists, told the International Court of Justice that her military hadn’t committed genocide against Myanmar’s minority Rohingya Muslim population. Without commenting on whether the extensively documented mass executions, rapes, village burnings, and other atrocities had taken place, or what role they had played in prompting hundreds of thousands of Muslims to flee her country, she said that her military had no “genocidal intent,” and had been responding to attacks by militants. Myanmar, she said, will handle the punishment of any soldiers who may have used “disproportionate force.”

Star Wars: Congress authorized the creation of a Space Force, a new branch of the military championed by Trump in the face of Pentagon skepticism. In last week’s newsletter I critically assessed Trump’s aspiration to preserve American “dominance” of outer space.

On a more positive note: The European Space Agency announced plans for humankind’s first ever removal from outer space of junk it has left there. And a week earlier ESA had said it would collaborate with NASA in an asteroid diversion mission that would test our ability to nudge asteroids headed toward Planet Earth onto a less destructive path.

Why Republican climate-change skepticism has grown as the planet has heated up

If you’re a liberal who has been trying to change the minds of conservative climate change skeptics, social science now offers this guidance: Cut it out! The first step toward convincing them that they’re wrong may be to quit trying to convince them that they’re wrong.

That’s one takeaway from a study presented last month by two political scientists, Dominik Stecula of Penn and Eric Merkley of the University of Toronto. They found that people who strongly identified as Republican and were shown the scientific consensus on climate change were less likely to accept it if they were also shown warnings about the perils of climate change from prominent Democrats.

By itself this isn’t big news. We’ve long known that, just as people sometimes use “in-group cues” to form their views—that is, they uncritically accept opinions prevalent in their tribe—they can also use “out-group cues,” rejecting opinions because they’re held by the enemy tribe. And you’d expect this effect to be especially strong in an age, like ours, of “negative partisanship”—when the two political parties seem to be held together largely by dislike of each other.

But Stecula and Merkley go further and suggest that the power of out-group cues may help explain an underappreciated fact: Republican skepticism about climate change has grown over the past two decades, even as evidence of global warming has accumulated. A 1997 survey, they note, found that 73 percent of people who strongly identified as Democrats believed that global warming was happening—and the corresponding number for people who strongly identified as Republicans was only slightly lower, at 68 percent.

In this view—though Stecula and Merkley don’t put it exactly like this—growing Republican climate change skepticism could be partly a product of negative partisanship. The more Republicans dislike Democrats, the less they’ll like the Democrats’ view of the world.

But this raises a question: If indeed the two parties’ views on climate change weren’t all that different in the 1990s, then how did concern about global warming get so strongly identified with Democrats that Republicans could react against it on partisan grounds?

Well, some divergence of view between the two parties was in the cards from the get-go. The generic policy implications of climate change—impose some form of regulation or restraint on energy producers and/or consumers—were bound to rankle Republican elites (politicians, pundits, big donors) more than Democratic elites. So cues from in-group elites should, by themselves, lead the Republican grassroots at least some distance toward climate change skepticism. And cues from out-group elites—warnings from high-profile Democrats about climate change—could help sustain that drift.

Which kind of elite cue—in-group or out-group—has played a bigger role in increasing Republican climate change skepticism? To shed light on that question, Stecula and Merkley looked at two kinds of evidence over time: the frequency of climate change pronouncements made by elites of both parties and reported in the media, and survey data that captured grassroots Republican attitudes toward climate change.

There’s no way of proving a causal link between the first of those variables and the second, no way of determining for sure that changes in elite signaling cause changes in grassroots attitude. But there is a statistical procedure that tells you whether changes in the former are predictive of changes in the latter—whether, if you know how much elites were talking about climate change at one point in time, that helps you guess what grassroots attitudes toward climate change will be at the next point in time. And the more predictive power these elite cues turn out to have, the stronger your grounds for suspecting that there’s a causal link. In stats jargon, this predictive relationship between variables is called “Granger causality.”

It turns out that cues from Republican elites—pundits and politicians speaking skeptically about climate change—have indeed “granger caused” growth in grassroots Republican skepticism. But this effect is weak compared to the effect of pronouncements from Democratic elites; when Democratic pundits or politicians warn about climate change, that really “granger causes” growth in grassroots Republican skepticism.

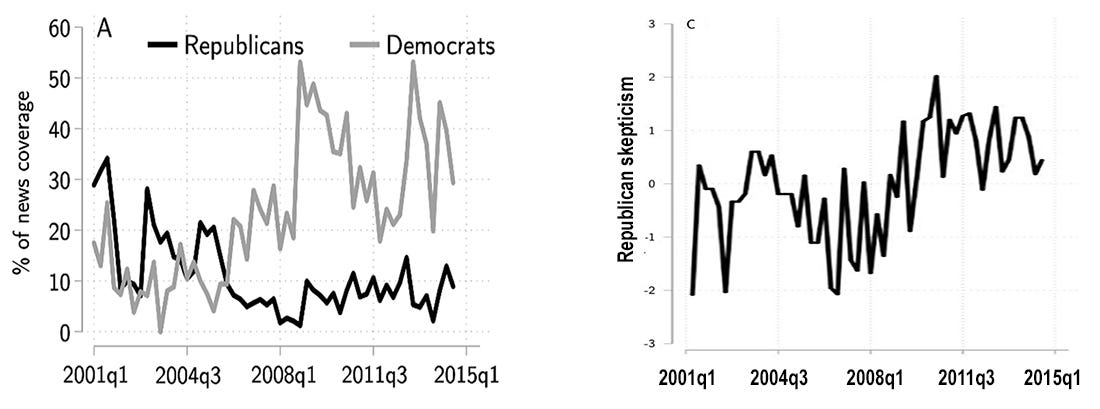

You can get a visual sense for this difference by looking at the graphs below. The one on the left charts cues from Republican and Democratic elites on climate change over time as reflected in the media. The one on the right charts grassroots Republican climate change skepticism over time. Note that when this skepticism takes a sharp upward turn—starting around the beginning of 2008 and continuing through that year—there’s been no big change in the frequency of Republican elite cues, but there has been a big jump in the frequency of Democratic elite cues.

As for what caused the upsurge in high-profile Democratic pronouncements on climate change: The authors don’t get into this, but it’s notable that Al Gore’s documentary An Inconvenient Truth won the Academy Award in 2007, helping to canonize climate change as a liberal talking point. With an election approaching in 2008, it would be natural for Democratic candidates and commentators to amplify that talking point.

I was kidding, kind of, when I said earlier that one takeaway from this study was that if you’re a liberal you should quit trying to persuade conservatives about climate change. For one thing, Stecula and Merkley were studying the role of elites in giving both in-group and out-group cues, and there’s a good chance that you don’t qualify for their definition of “elite.” (Sorry—there was no way to break that to you gently.)

Still, in-group and out-group cues can also operate at the grassroots level, even if that wasn’t the subject of this particular study. And awareness of the power of out-group cues in an age of negative partisanship might usefully inform your online behavior.

For example: If you’re thinking about challenging someone’s climate change views online, you might consider bending over backwards to convey civility and respect. Granted, that’s not new advice. But it makes particular sense at a time when liberals and conservatives hold such negative stereotypes about each other that just being polite could, by defying stereotype, weaken the perception that you’re part of the enemy tribe—and so make your message less likely to register as an out-group cue.

And, if you’re a liberal elite (you know who you are!), well…I’ll let Stecula and Merkley take over here. They see their findings as suggesting that “party elites who strongly identify with the scientific consensus on climate change” should “weigh the costs and benefits of aggressively communicating their stance in the mass media.” Of course, making the case for climate change concern on TV or radio is a job somebody’s got to do. But if, when CNN calls, you can politely demur and steer the booker toward a Republican elite who worries about climate change, you’ll be doing your tribe a service.

To share the above piece, use this link.

Stephen Batchelor’s Secular Buddhism: Embrace, Let go, Stop, and Act

In the past two issues of NZN we’ve run excerpts from classic conversations I’ve had on my audio podcast, The Wright Show (which are also available in video form at meaningoflife.tv and on the meaningoflife.tv YouTube channel). If we’re correctly reading the statistical feedback (more clicks is better, right?), these excerpts have been popular. So here’s another one—an excerpt from a conversation I had three years ago with Stephen Batchelor, whose seminal book Buddhism Without Beliefs made his name nearly synonymous with “secular Buddhism.” You can read the whole excerpt here. To give you a sense for what you’ll find there, here’s an excerpt from the excerpt, in which Stephen discusses the importance of thinking about the historical context in which the Buddha lived:

Emphasizing the human Buddha, humanity of the Buddha is one of several hermeneutic approaches whereby we have a way to separate out the stuff that has to belong to ancient India, ancient Indian culture, belief and so on, and the things that the Buddha said that we cannot derive from that context, that seem to be the result of his own experience, his own insight, his own vision.

And the reason I find these elements most engaging is because they tend to be the most radical elements. There's very little religiosity in them. It's very difficult, when you imagine the Buddha living in his time, in India, at that period, to see anything going on there that would correspond to what we call "religious" today.

It's a bit like Jesus and his disciples around the Lake of Galilee. If you could see them from Mars or something, it wouldn't look like a religion. It would be much closer, in fact, to what we might find in Greek philosophy. I think the Buddha is very close in spirit and in style and many other things to people like Pyrrho, Epicurus, the Stoics—again, which we don't think of as religious. They're practical philosophies that are not reducible to simple techniques.

And here, I think mindfulness we do have to treat with some caution because we single it out as though it's the be-all and the end-all of the Dharma. It's not. It's operative within the ELSA framework. Embracing the world, Letting go of reactivity, Stopping, Acting. It's embedded within ethics. It's embedded within a philosophy, which is far more than just paying attention and being here and now in the moment.

In Aeon, the philosopher Nicolas Bommarito sings the praises of modesty and explains why, historically, many philosophers haven’t been big fans of it. Bommarito’s conception of modesty seems in some ways eccentric; he says that truly modest people don’t really care how they stack up against other people. (I’ve always tried to be modest, but if that kind of indifference is a prerequisite, I give up.) But at least one of Bommarito’s claims is unarguable: Modesty, he says, “is something you can’t really brag about.”

This week the Washington Post published and assessed a trove of government documents that are to the Afghanistan War what the Pentagon Papers were to the Vietnam War: a look into government findings and deliberations that reveal much more internal doubt about the prospects for success than was officially acknowledged.

In the Post’s Outlook section, Stephen Wertheim and Samuel Moyn of the Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft explain how the disregard of both domestic and international law has led war—invasions, occupations, drone strikes, special forces raids, etc.—to become a post-Cold-War constant for America.

Elon Musk drew a certain amount of ridicule for this tweet. But I actually found it interesting. I’d never before thought about using one interpretation of quantum physics—that subatomic reality doesn’t assume definite form until it’s observed—to buttress the hypothesis that we’re living in a simulation. (And hey, at least he didn’t call anyone a pedophile.)

Have you ever noticed that different trains’ whistles have different pitches? Turns out they’re so different that you could, by creating a video mashup of different trains whistling, play Pachelbel’s Canon.

And finally: People often (OK, OK, sometimes) ask how they can support this newsletter. Well, let me count some ways:

1. Follow us on Twitter—and (this part is really important) retweet some of our flagrantly self-promotional tweets. Or come up with your own flagrantly promotional tweets about our content and include our twitter handle (@NonzeroNews) and/or my twitter handle (@robertwrighter) so that your tweets will fill us with a warm glow.

2. Share this newsletter via the share button below, or share components of the newsletter by using the nonzero.org URLs you get when you click headlines and/or colored subject-heading bars above.

And if you want to support us financially, there’s always the Patreon page, via which you can help sustain not only the newsletter but various other creations of the Nonzero Foundation.

One feature of becoming a Patreon patron is that you can watch the occasional Patreon-only video. For example: I followed up on last week’s Ask a Russian initiative by having a conversation with the Russian in question, NZN artist-in-residence Nikita Petrov. We talk about the different kinds of freedom of speech that Russians and Americans enjoy, the breakdown of elite control of American parties, the state of contemporary art, and one shaman's lonely crusade against Putin.

OK, that’s it for this week. See you next week!