Death to the aiding-and-abetting meme!

Plus: Trump’s Wuhan lab theory backfires; Is physical stuff all there is?

Welcome to another NZN. In this issue I: (1) declare war on a rhetorical tactic, insidiously deployed in the latest issue of the Atlantic, that I claim has brought much death and suffering; (2) explain why Trump’s insinuations about the coronavirus having originated in a Chinese lab may come back to haunt him; (3) explore, with philosopher Gideon Rosen, the question of whether physical stuff is all there is; and (4) steer you to readings on such things as: pandemic-ready robots; evidence that cable news viewing habits can accelerate or slow the pandemic; and an argument that the current moment in history has anti-war tendencies.

Let’s kill the aiding-and-abetting meme once and for all!

This week I read a piece in the Atlantic that gave me a new mission in life. I now want to stamp out—completely extinguish, with no mercy whatsoever—a rhetorical tactic that has long belonged in the dustbin of history but continues to plague humankind: the aiding-and-abetting meme. That is: depicting people whose views you don’t like as being in league with, or abjectly serving the interests of, adversarial foreign powers.

The Atlantic piece is by George Packer, and the folks at the Atlantic think so highly of it that it’s in the actual physical magazine. Here’s a passage from it:

Donald Trump saw the crisis almost entirely in personal and political terms. Fearing for his reelection, he declared the coronavirus pandemic a war, and himself a wartime president.

OK, so far so good. But then Packer continues:

But the leader he brings to mind is Marshal Philippe Pétain, the French general who, in 1940, signed an armistice with Germany after its rout of French defenses, then formed the pro-Nazi Vichy regime. Like Pétain, Trump collaborated with the invader and abandoned his country to a prolonged disaster.

I realize that, to many readers, it won’t be obvious why this passage sent me over the edge, catapulting me all the way into Howard Beale territory. So let me try to explain the several things about it that, together, gave it such force.

1. The passage makes no sense. If I understand Packer correctly, he’s saying that Trump “collaborated with”… a virus? Collaborating with another being means helping it in exchange for its helping you. Does Packer really mean that Trump wanted the virus to kill lots of Americans and tried to facilitate that? (Leaving aside the question of whether the virus fully comprehended the terms of the deal, as befits a true collaborator.)

Look, I wouldn’t put it past Trump—or lots of other politicians—to countenance mass death for the sake of political gain. But there are so many reasons to doubt this particular evil-genius scenario (beginning with the genius part) that I won’t waste time listing them.

Maybe I’m being pedantic. Isn’t a gifted writer allowed to deploy metaphors loosely? Indeed, doesn’t Packer get extra points for his sly creativity? After all, he managed to hint that Trump has Nazi sympathies while putting this innuendo in such an absurd context that no one can reasonably demand that he defend it! Shouldn’t I cut Packer some slack, especially since he and I are both on the anti-Trump team?

No, no, no! No mercy! That’s my point—I’ve been driven all the way to a zero-tolerance policy. And, yes, I realize that it still may not be clear to you why my reaction to Packer’s piece is so extreme. Which leads to reason number two:

2. The author of Packer’s piece is Packer. George Packer was among the prominent liberal hawks who famously and influentially advocated the disastrous 2003 invasion of Iraq. You may ask: But isn’t 17 years long enough to forgive and forget? Forgive yes, forget no. If we want to avoid such blunders in the future, we have to remember the things that led to them. One such thing was enslavement to an American-o-centric view of the world—specifically, failing to consider how invasion and occupation might be perceived by the various different groups that constituted the Iraqi nation. And I don’t think it’s a coincidence that someone who failed to adequately ponder that question is a promiscuous deployer of the aiding-and-abetting meme. Because….

3. The aiding-and-abetting meme is routinely deployed to discourage departing from an American-o-centric view of the world. For example:

In 2004, Jonathan Steele, writing in the Nation, tried such a departure. He argued that an election in Ukraine viewed by Americans as “a struggle between freedom and authoritarianism” was more complicated than that; the candidate America was supporting by bankrolling websites and radio stations and deploying political strategists was actually opposed by lots of Ukrainian voters. And, Steele noted, America’s attempt to sway the election, viewed from Moscow, didn’t look like an innocent exercise in democracy promotion. Steele opined that “Ukraine has been turned into a geostrategic matter not by Moscow but by Washington, which refuses to abandon its Cold War policy of encircling Russia and seeking to pull every former Soviet Republic into its orbit.”

A writer in the New Yorker, rather than try to dispute that claim (as would ideally happen in reasoned debate), deployed the aiding-and-abetting meme. He noted that this piece in the Nation aligned with the views of one Vladimir Putin and said that the Nation was “once again taking the Russian side of the Cold War.” And the New Yorker writer who said that was…George Packer!

By then—nearly two years after the Iraq invasion—Packer was having second thoughts about the wisdom of the invasion, yet he hadn’t abandoned the perspective that led to it. He was still determined not to see things from the point of view of America’s adversaries—so determined, apparently, that he wanted to stigmatize people who tried such a thing.

Packer and his ilk carried the day. Fully a decade later, America was still trying to sway elections in Ukraine, and the average member of the American foreign policy establishment (aka The Blob) was still unable to imagine how this might look from Moscow. In 2014, when a democratically elected Ukrainian president supported by Russia was deposed under threat of violence, fled the country for his life, and was replaced by a government led by a man who had been hand-picked by the US for that role, American foreign policy elites celebrated as if we had just witnessed democracy in action.

Putin was less thrilled. He responded by occupying and annexing Crimea and supporting violent separatists in eastern Ukraine, thus condemning Ukraine to its current tortured state. This reaction shocked Americans more than it would have if people like Steele had been taken seriously rather than marginalized by people like Packer.

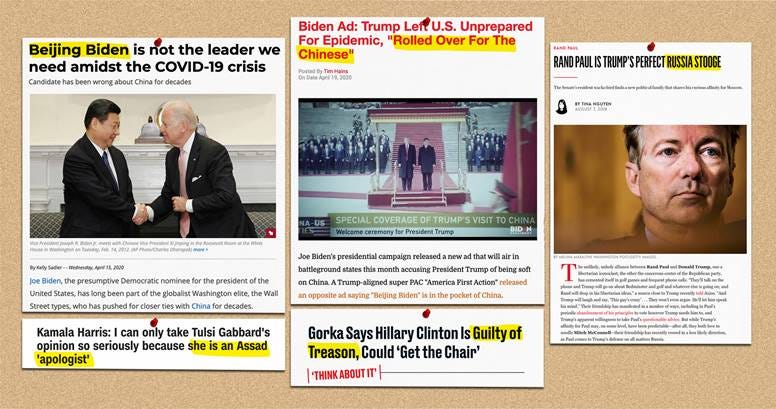

And so it goes in American political discourse. If you raise questions about, say, the wisdom of America’s arming rebels in Syria, you are an Assad sympathizer and a Putin stooge. If you argue that engagement with China makes sense in spite of its human rights record and its lack of transparency (oops, I meant to say, its cover up) during the first phase of the Covid contagion—well, obviously, your allegiances are suspect.

It’s testament to the power of the aiding-and-abetting trope that this latest version of it is being harnessed by both sides in the presidential campaign. On the one hand is the suggestion—made by Trump and some of his supporters—that Joe Biden is a servant of China’s conniving rulers, and on the other hand is the suggestion—made by Biden and some of his supporters—that Trump is a servant of China’s conniving rulers. So we can look forward this campaign season to an arms race of Chinaphobia at a time when various challenges—like fighting a pandemic without ushering in a global depression—call for international cooperation.

Which brings us, finally, to a few kind words about George Packer. I guess he deserves credit for suppressing any temptation to join this arms race, to play the China card against Trump.

But what does it say that this suppression seems to have become sublimation—that the impulse to deploy the aiding-and-abetting meme was so strong that, denied one kind of expression, it just surfaced in new and bizarre form, as an accusation of collaboration with a virus?

I think that’s what sent me over the edge: the thought that this primitive, tribalistic rhetorical tactic, which by all rights should have been discarded forever on the glorious day that Joseph McCarthy was censured by the Senate, remains as stubborn and hard to eradicate as, say, the virus Trump is allegedly collaborating with.

I’m not calling for an end to discussion of foreign influence on American politics. It's fine, for example, to point out that various foreign interests try to steer American policy to their ends. But these discussions should involve high standards of evidence, should avoid gratuitous personal attacks, and should always coexist with an awareness that the US, too, tries to steer policy in other countries to its ends.

What should be strenuously avoided—and called out when it appears—is the use of cheap emotionalism to constrict our field of vision, to imprison us in the American-o-centric solipsism that has brought much death and suffering, has failed to serve America’s interests, and that, nonetheless, continues to guide American foreign policy.

If you agree with me that the world would be a better place if the aiding-and-abetting meme were squashed, please help squash it by sharing this piece on social media via this link.

How Trump’s “Wuhan lab” theory is backfiring

The theory that Covid-19 came not from a Chinese “wet market” but from a Chinese laboratory now has the full support of President Trump. This hasn’t been confirmed by Trump himself, but it’s been confirmed by the next-most-official source: a Fox News chyron. During a recent episode of Tucker Carlson’s show, the chyron read, “Sources to Tucker: Intel agencies are almost certain that the virus escaped Wuhan lab.”

In sheerly factual terms, Trump could turn out to be on solid ground. The fringe version of this theory—that the virus came from a bioweapons lab, and may have been genetically engineered—continues to be widely dismissed, but credible people think the virus could have escaped from a less nefarious Wuhan lab, one that studies coronaviruses with an eye to preventing epidemics.

I can see why Trump thinks that publicizing even this watered down version of the lab origin story is a political winner. Though it lacks the cinematic flair of the bioweapon theory, it seems (at first glance, anyway) to corroborate the idea that the Chinese government was engaged in a cover up during the contagion’s crucial early stages. So it reinforces Trump’s blame-the-perfidious-Chinese-communists-not-the-incompetent-American-president narrative—without Trump having to be the one who blames the perfidious Chinese.

But if I were Trump I’d hope that the lab origin story doesn’t pan out. On close examination it turns out to reinforce the blame-the-incompetent-American-president message. In 2018, we now know, the Trump administration had an opportunity to help tighten security at the Wuhan lab that is at the center of the story and failed to do so.

Earlier this month Trump supporters hailed a piece by Washington Post writer Josh Rogin that seemed to lend substance to the lab origin story. Rogin reported that in 2018, US officials paid repeat visits to the Wuhan Institute of Virology. The WIV lab has the highest biosafety rating available—P4—but the US visitors came away with doubts that it was safe enough, given the highly infectious and lethal viruses it was studying.

A cable drafted by US diplomats in China, sent to Washington in January of 2018, and obtained by Rogin reads as follows: “During interactions with scientists at the WIV laboratory, they [the Americans who visited the lab] noted the new lab has a serious shortage of appropriately trained technicians and investigators needed to safely operate this high-containment laboratory.” A second cable, also sent to Washington, carried the same basic message, according to Rogin.

Trump supporters who amplify this part of Rogin’s story tend not to mention a second part of it. Both cables, Rogin writes, “argued that the United States should give the Wuhan lab further support, mainly because its research on bat coronaviruses was important but also dangerous.”

And China was asking for such support. Notwithstanding the vision of this lab cultivated by conspiracy theorists—a black box where God knows what was going on—it was a lab whose workers had long collaborated with American scientists. Rogin writes: “The Chinese researchers at WIV were receiving assistance from the Galveston National Laboratory at the University of Texas Medical Branch and other U.S. organizations.” And now, “the Chinese requested additional help”—help that the authors of the State Department cables advocated for the sake of America’s, and the world’s, security against a possible contagion.

And what did the Trump administration do in response to these pleas? Nothing.

Why? Who knows? Maybe the contagion of incompetence that Trump unleashed within the executive branch three years ago resulted in the two cables not getting the attention they deserved. Maybe Trump’s secretary of state read them and deep-sixed them. Maybe they reached Trump and he ignored them. In any event, it’s Trump’s administration and the State Department is run by his appointees—so it’s Trump’s fault.

So if it turns out that the virus escaped from this lab, then the administration’s unresponsiveness to these cables is, by any rational reckoning, a huge political deal.

Two footnotes:

(1) If indeed the virus escaped from a lab, that wouldn’t mean the Chinese government purposefully misled us in advancing the “wet market” theory. In one scenario apparently leaked by the Trump administration to Fox News so that Trump could conspicuously refrain from denying it, an intern at the lab transmitted the virus to her boyfriend, and he then went to the wet market and spread the virus. In any event, various pieces of evidence indicate that Wuhan officials emphasized the wet market theory in conveying news of the crisis to China’s national government.

(2) The kind of transparency this laboratory had—US scientists collaborating on the work there, US officials visiting it—is something you can probably kiss goodbye if this pandemic leads to a new Cold War with China, as various Republicans seem to want and as some of Joe Biden’s campaign messaging may encourage.

To share the above piece, use this link.

Is physical stuff all there is? If you ask a philosopher that question, it can lead to a discussion that covers things ranging from consciousness to 20th-century physics to whether mathematical concepts are real. That’s what happened when I discussed the subject with Gideon Rosen, professor of philosophy at Princeton and co-author of The Norton Introduction to Philosophy. Gideon is also a friend of mine—which made the conversation even more fun for me than it would have been otherwise.

ROBERT WRIGHT: I've been trying to get you to be on this show for years. You've resisted, but the reason I've wanted you to is that whenever I have a question about philosophy, you provide a very efficient overview of the whole context of my question. You don't always provide a definitive answer, but that's in the nature of philosophy.

GIDEON ROSEN: It is. It's a shame that it's in the nature of philosophy.

It would be nice if we could wheel out definitive answers to these questions and it's a bit of a mystery why we can't, since everybody else manages to provide the occasional definitive answer. We don't. It's a drag, but we do our best.

Do you think it's a mystery? Or do you think it's kind of clear, given the nature of the questions you address, why it would be the case that you don't come up with the same kinds of answers that mathematicians and scientists do?

Yeah, there are some obvious differences that explain why we don't do it the way they do—but, if the questions make sense, if the questions are clear, then they have answers. We don't have a clear sense of why it is that we can't nail them down.

It's not as if we're floundering around. Philosophy produces plenty of opinion, plenty of conviction—even plenty of justified conviction, in the sense that people have arguments for their views and arguments that some people find persuasive. But we don't get as much consensus on the hard questions, even given the arguments we've got, and that's a little mystifying...

I don’t know, I want to give you more credit. I think you're just tackling the hard questions…

I wanted to start out on the question of materialism or, as I guess it's more or less interchangeably called, physicalism. Let me give you the crude definition and then you can correct me. It's ... the idea that everything that there is is physical, it's material stuff…

People of a religious or spiritual persuasion…often think of the worldview of materialism as being antagonistic to their worldview, and a lot of people see it as maybe depressing...And a question arises: what is the status of the worldview of materialism within philosophy?

Why don't you start out by telling me what you think of the words “physicalism” and “materialism” as meaning, and then we can get into the status of the idea.

Hardheaded philosophers who are impressed by the scientific worldview used to call themselves materialists. That's because they thought that what science had shown is that, at the fundamental level, absolutely everything is made of matter, where “matter” is something that we have a pretty good ordinary idea of.

We know what rocks are like. We know what clay is like. That stuff takes up space. It's spread out, it has geometrical properties. It's impenetrable, and so on. The rocks and the clay of ordinary experience may have other features too, like color and smell, which are a sort of subjective contribution on our part.

But you abstract from that, and what's left is this pretty clear conception of material stuff with geometrical properties that takes up space and has properties like mass, and so on. And for a long time, physics seemed to be saying everything at the fundamental level is like that. It's just geometrical space-occupying stuff, maybe spread out in some empty space.

That was materialism. And that was the received view of what physics, or physics and chemistry, had shared about nature for a long time.

And then that view started to fall apart in the middle of the 19th century, because what physics then seemed to be saying was, it's not all like that. There is, for example, the electromagnetic field.

The electromagnetic field is not like a rock. It's spread out. It's everywhere. It's thin. It's filmy. The features that scientists attribute to it aren't features like [knocks on the table] bang-on-the-table impenetrability. So physics is telling you that that's what nature is like at the most fundamental level. It's not telling you that nature is material at the fundamental level. But it is telling you that nature is physical at the fundamental level.

But then what does the term mean at that point?

You can read the rest of this dialogue at nonzero.org.

In the Atlantic, Peter Beinart argues that the Biden campaign’s apparent decision to try to out-hawk Trump on China suffers from three shortcomings: “First, it promotes bad foreign policy. Second, it could stoke anti-Chinese racism. Third, it doesn’t even make long-term sense politically.” But aside from that…

The Verge reports that Spot, the doglike robot made by Boston Dynamics, is being used in hospitals to reduce the risk of transmitting the coronavirus between patients and staff. Ars Technica, in a piece called “The pandemic is bringing us closer to our robotic future,” notes that wheeled sidewalk delivery robots are also in demand.

In Foreign Affairs, political scientist Barry Posen argues that, though the pandemic has in some ways heightened international tensions, “the odds of a war between major powers will go down, not up.”

In a University of Chicago working paper, four academics present evidence that cable news viewing habits have influenced patterns of Covid-19 infection. During February, when Tucker Carlson was warning about the Covid threat and Sean Hannity was dismissing it, the more a county’s Fox News viewers watched Hannity, and the less they watched Carlson, the more the county was afflicted by the epidemic. This pattern abated after late February, when Hannity started taking the virus more seriously.

In the New York Times, Thomas Edsall assesses the political logic behind Trump’s attempt to play both sides of the lockdown debate—supporting people in Michigan, Wisconsin, and Virginia who rebel against restrictions that are remarkably like the restrictions he professes to support.

In Vox, Roge Karma interviews Yale historian Frank Snowden, author of Epidemics and Society, about why the modern world is so vulnerable to pandemics and how the current pandemic will affect the perennial struggle between xenophobia and tribalism on the one hand and cosmopolitanism and cooperation on the other.

In the Guardian, Julian Borger does a play-by-play recounting of the World Health Organization’s response to the coronavirus contagion (and in the process rebuts widespread reports that Taiwan offered early evidence of human-to-human transmission that was ignored by WHO).

In the New York Times, Taylor Lorenz looks at Josh Zimmerman, who is a “life coach for influencers.” Weeks into the pandemic, a client who has big followings on YouTube and Instagram asked him for guidance and “within 24 hours… she had a plan for a timely series about grief, gratitude and self-reflection called ‘14 Days of Mindfulness.’ ” Lorenz opines that “Mr. Zimmerman’s role feels especially vital now, in the midst of a health crisis that has sent half the world home for an indefinite period and glued many of them to their phones.”

The Guardian reports that books by Marcus Aurelius and other Stoic writers are selling well amid the pandemic. Marcus, who lived through a plague, advised that, rather than mourn your bad luck amid misfortune, “you should rather say: ‘It is my good luck that, although this has happened to me, I can bear it without pain, neither crushed by the present nor fearful of the future.’ ” I’ve always assumed it would be easier to adopt that attitude if I were emperor of the Roman Empire, but maybe I’m underestimating the demands of Marcus’s job.

OK, that’s it! Hope you’re bearing adversity stoically. You can follow us on Twitter here, email us at nonzero.news@gmail.com, and share our content on all known social media (which we very much appreciate). See you in a couple of weeks, give or take.

Illustrations by Nikita Petrov.