Some useful Trump-Hitler comparisons (in light of Minneapolis and Venezuela)

Plus: AI updates and the graph of the week

On Wednesday, during a conversation with my NonZero colleagues about America’s attack on Venezuela and the Trump administration’s hints that Greenland might be next, I said, half-jokingly, something like, “Who’d have guessed that a year into the Trump administration we’d be talking about comparisons with Hitler’s foreign policy, not with Hitler’s domestic policy?” That same day, an ICE agent in Minnesota killed Renee Nicole Good, turning attention back toward Hitler’s domestic policy.

Before going further, I should invoke the standard disclaimers. No, Trump isn’t Hitler. He’s not, for example, trying to kill all Americans who belong to a particular ethnic group. And if he were slavishly following Hitler’s recipe for international aggression, he’d have invaded not Venezuela but Canada, vowing to liberate our fellow English speakers from the yoke of Francophone oppression.

Still, as the one-year anniversary of Trump’s second swearing in approaches, there are clear causes for concern on both the domestic and international fronts. And I think listing some similarities and differences between Hitler and Trump along these dimensions can be clarifying even if the differences outweigh the similarities.

Let’s start with those men in Minneapolis who are sometimes referred to as jack-booted thugs. Now, obviously, that label isn’t entirely apt; ICE agents aren’t the SS or the SA. Still, none of the 11 other presidents I’m old enough to remember sent swarms of armed men wearing masks into America’s cities with broad license to stop and even detain people without granting them the courtesies that real police are supposed to grant.

For example, on Wednesday an armed, masked man walked rapidly toward Renee Good’s car saying, “Get out of the car, Get out of the car, Get out of the fucking car!” and, when he reached his destination, grabbed her door handle as if he was about to yank her out of the car—at which point she, fatefully, tried to drive away. Why, when I was a boy—and for that matter when I was a middle-aged man—law enforcement officers were expected to approach cars in an unthreatening manner and say things like, “Ma’am, could you please get out of the car?” Also, these law enforcement authorities, rather than wear masks that concealed their identity, typically wore badges with ID numbers on them. If all those bygone customs still applied, Renee Good probably wouldn’t have freaked out and tried to flee and so would still be alive.

Trump has signaled clearly to ICE agents that he doesn’t expect old-fashioned decency from them. Two months ago, during a 60 Minutes interview, Norah O’Donnell asked him about “videos of ICE tackling a young mother, tear gas being used in a Chicago residential neighborhood, and the smashing of car windows. Have some of these raids gone too far?” Trump said, “No, I think they haven’t gone far enough, because we’ve been held back by the judges, by the liberal judges.”

I’m guessing Trump takes delight in having the power to deploy large numbers of ICE agents (“the toughest men you’ll ever meet,” he lovingly calls them) and then watch them defy or even intimidate his ideological adversaries—the people who show up at big ICE raids to protest or monitor them (which Good, who lived in the neighborhood being raided by ICE, was doing). That would help explain why he keeps sending the toughest men you’ll ever meet to states and cities run by Democrats. As a Wall Street Journal piece about the Renee Good shooting put it, “The tragedy delivered yet another chapter of Trump vs. Minnesota, a protracted saga that has become emblematic of the president’s targeting of Democratic strongholds.”

That Trump targets ideological adversaries doesn’t make him Hitler, whose brownshirts did such targeting much more brutally and systematically. But it does point to a path by which America could get closer to Hitler-level authoritarianism. Incidents like the Renee Good killing can trigger mass reactions that Trump deems unruly enough to warrant countermeasures—Army deployments or National Guard deployments or additional ICE agents or maybe even loosened rules of engagement. (The New York Times reports that 100 more federal agents are now headed for Minneapolis.) Those countermeasures can lead to more mass reactions, more countermeasures, and so on. The danger of Trump, on the domestic front, isn’t that he’s Hitler or aspires to become Hitler, but that he has enough in common with Hitler to set in motion a very negative kind of positive-feedback cycle and then happily do what he can to sustain it, making good use, at key moments, of his contempt for the principles of liberal democracy.

The joy Trump takes in the use of intimidating force extends from the domestic arena into the international arena. Indeed, it’s hard to explain the escalating holiday-season campaign against Venezuela—boat bombings, then a port bombing, and finally invasion—without invoking this kind of visceral motivation. After all, Venezuela isn’t the country you’d go after if drugs were your real concern. And as for oil: The basics of the administration’s current plan for Venezuela—leave an authoritarian regime in place but profit from its petroleum—didn’t require invading the country and snatching Nicolas Maduro; Maduro himself had agreed to that kind of deal. And, though Trump can presumably get somewhat better terms now than he’d have gotten from Maduro, there seems to be a consensus among oil experts that the foreseeable benefits are meager; with oil prices low, and Venezuela still a shaky place, US companies won’t want to make the big investments required to extract oil in large quantities.

I doubt I’ll ever see a man more evidently full of pride and self-satisfaction than Trump is when he’s talking about his various unprovoked international assaults—the assassination via missile strike of Iran’s top general during his first term, the bombing of Iran last year, the attack on Venezuela last week. But I’m guessing that if I spoke German and combed through some recordings of Hitler in the wake of the Poland invasion I’d come close.

That said, the differences between the Poland and Venezuela invasions are big and in some ways reassuring. The Venezuela incursion was basically a huge special ops exercise, with all US troops exiting the country shortly after entering. And that’s the way Trump likes it. He said afterwards that if the new(ish) regime doesn’t comply with his dictates, “We’re not afraid to put boots on the ground.” He doth protest too much; he’s famously averse to putting boots on the ground in an enduring way. And that, by itself, is a good thing.

But a slide toward a big war can be like a slide toward authoritarianism; you get propelled into hell by some sort of positive feedback cycle. And the thing about Trump’s low-commitment military strikes is that they invite repetition. If Trump judges the Venezuelan incursion a political success—or for that matter is just overwhelmed by the sheer thrill of the thing—the obvious question becomes: Why not do Colombia? And the more of these things you do, the more opportunities there are for things to spin out of control.

Defenders of Trump’s foreign policy imagine it leading to global stability. In this scenario, the world is divided into spheres of influence, and superpowers like the US, China, and Russia serve as regional police. So long as they stay out of each other’s neighborhoods, there’s no war among superpowers.

Well, maybe. On the other hand, if each superpower likes throwing its weight around as much as Trump does, this multipolar world will feature recurring opportunities for things to go badly awry. And Trump has increased the chances of that happening by doing so much to erode respect for the norm against—and the international law against—transborder aggression.

He’s not alone in this culpability. Most post-Cold-War presidents have attacked a country in violation of the UN Charter (which, by the way, is a treaty that the US Senate ratified—and the US Constitution says that treaties ratified by the Senate become the law of the land). But Trump’s violations of international law are distinctive in their quantity and, especially, in their brazenness; he explicitly rejects the principle of respecting borders. I’m as annoyed as anyone by the hypocrisy of presidents who extol the “rules based order” while breaking the rules, but I do think this kind of hypocrisy, in moderate measure, is less damaging than Trump’s open celebration of lawlessness. And I agree with commentators in such august publications as the New York Times and the NonZero Newsletter who say that the norm of respecting the law against transborder aggression is now weaker than it’s been in a long time.

It should go without saying that Trump’s disregard for the sovereignty of other nations (except the powerful ones) is something he has in common with Hitler. And there’s a deeper commonality underlying this commonality: the belief that might makes right.

For Hitler, this was a stated philosophy, based on the famously flawed inference of “ought” from “is” that’s known as the naturalistic fallacy. The fact that the strong dominate the weak in the natural world, Hitler believed, means it’s good for the strong to dominate the weak. Nature, he wrote, “confers the master’s right on her favorite child, the strongest in courage and industry.”

Trump isn’t as explicit about the philosophical foundation underlying his exaltation of strength. In fact, it’s not clear that he thinks it’s good that the world is a place where the strong dominate the weak and violate whatever rules they can get away with violating. He may just think of himself as a kind of rational realist—someone who sees the harsh truth about how the world works and makes the most of it. Still there’s an implied philosophy here—a kind of nihilism.

You can certainly argue that Trump’s kind of nihilism is preferable to Hitler’s guiding philosophy. In fact, I’d argue that myself. But what the two world views have in common is a deep respect for the law of the jungle. And that’s also something Trump’s conduct on the international stage has in common with his conduct on the national stage. Which is why recent events in Venezuela and Minneapolis are genuinely ominous.

On Thursday White House AI and Crypto Czar David Sacks declared that reports of AI’s negative impact on American employment have been greatly exaggerated. He cited encouraging jobs data from October and November. But the next day brought news that, as a Wall Street Journal headline put it, “Job Gains Cooled in December, Capping Year of Weak Hiring.” And notably, notwithstanding this weak hiring (584,000 new jobs, compared with 2 million the previous year), “economic growth has remained strong,” the Journal observed. This combination—declining job growth amid persistent economic growth—is exactly what you’d expect if indeed AI is decreasing the need for workers by increasing per-worker output (i.e., increasing productivity).

That said, there isn’t much evidence of AI-driven productivity growth. But I have a theory about that, and if I’m right it could mean rough times are ahead for job seekers. Maybe, though most companies haven’t yet applied AI to great effect, many workers are finding valuable uses for it—and then secretly pocketing the gains. In other words, they spend less time working and more time goofing off but deliver as much as ever to their bosses. So productivity is growing but not in ways that are showing up in the statistics. This kind of concealed productivity growth can’t go on forever, and I think this may become evident in 2026.

In any event, if 2026, like 2025, brings much better news on the economic growth front than on the jobs front, that will add to the reasons to think that the AI accelerationism championed by Sacks—and by JD Vance and by Trump himself—could become a political liability of growing magnitude.

Researchers at Stanford this week published a finding that may be good news for the New York Times and other publishers that are suing AI companies for copyright infringement: Though large language models don’t make verbatim copies of the texts they ingest during training, large intact stretches of text can be extracted from them if you use “jailbreaking” techniques.

But the different models seem to vary greatly in their extraction potential. The researchers got Anthropic’s Claude Sonnet 3.7 to cough up 96 percent of Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone, whereas ChatGPT 4.1 gave them only 4 percent. Of course, literary purists may turn their noses up at Claude’s offering, saying there’s no point in having only 96 percent of a novel. And I’m guessing that ChatGPT’s 4 percent doesn’t happen to be the 4 percent that Claude is missing.

Banners and graphics by Clark McGillis.

Both Russia and China condemned the attack on Venezuela, citing international law, (a tad rich, at least on Russia's part) but if I was them I would have made full use of it. China/Russia could have said:

"We fully support America's removal of an illegitimate president of a rogue state ... and, ah, we will shortly be doing the same to Taiwan/Ukraine. We look forward to USA's full support in this matter. Go USA!"

Detail... but "these law enforcement authorities", as you describe them, are wearing masks because those opposed to their actions began doxing them thereby threatening their families. There has been significant interference with ICE's mandate but I am not aware of anyone being arrested and charged with obstruction of justice. Yes, Trump has done a lot to erode respect for conforming to the law, both intra- and internationally but emulating him by mistreating ICE agents is not the right response.

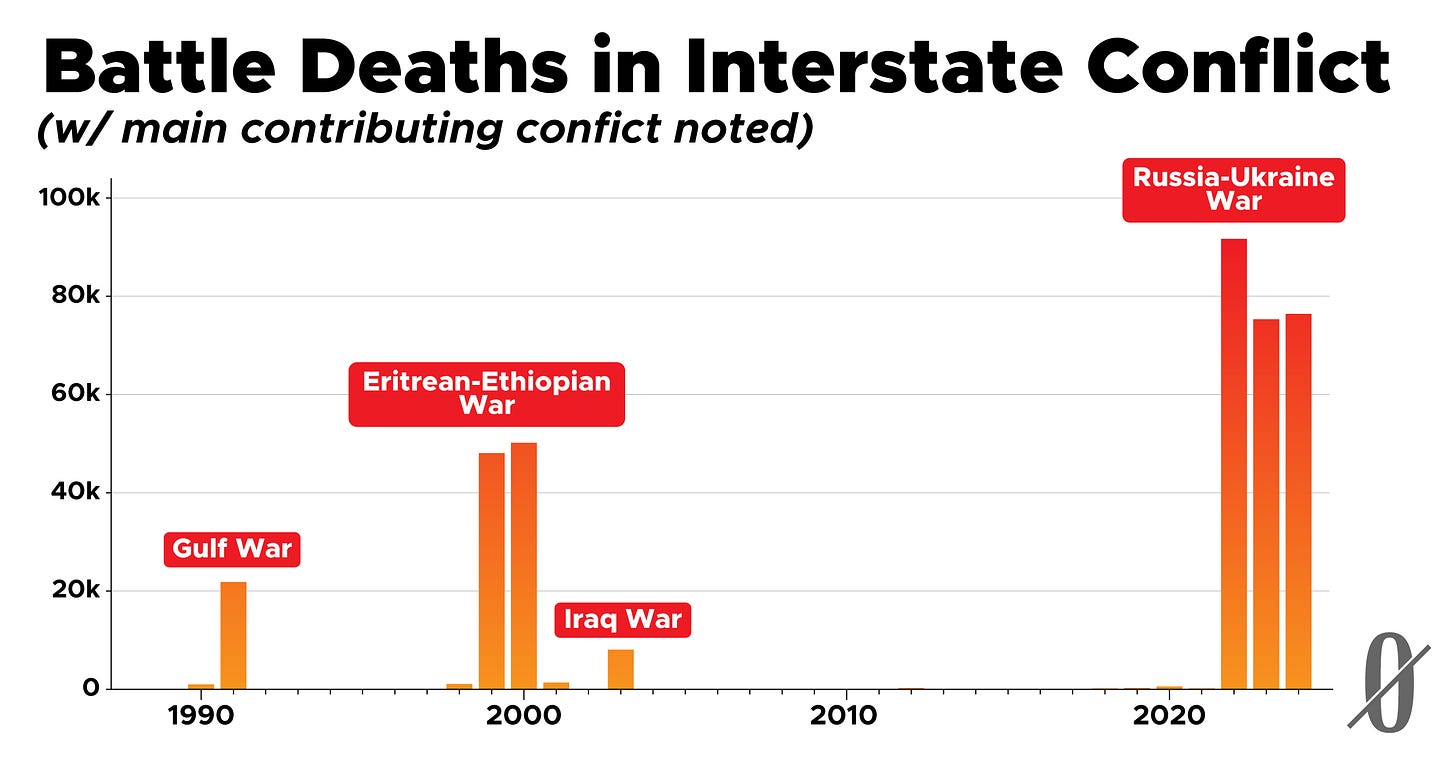

Another detail.... Some people (myself included) voted for Donald Trump simply because of his commitment to end the senseless Ukrainian conflict. His verbiage suggested that he would restrain the American Empire worldwide, something to which Tulsi Gabbard has been deeply committed. I wonder how she feels now after Trump's various military forays.