The China Chip Rorschach Test

Plus: Neocon Monroe doctrine; Screw Mars; Disney's AI gambit; and more!

The reaction to this week’s announcement that the US will sell advanced AI chips to China has revived an uneasy feeling I get from time to time. It’s the feeling that, though there is a wide spectrum of elite opinion about how we should handle AI, none of the opinions make sense.

That’s a slight exaggeration. I can point to individual people whose views on AI seem well thought out. What I can’t point to is a sizable block of influential elites with such views—a faction that has much clout, or even gets much airtime. And it seems to me that the elites who do have influence are steering us toward a probably bad future.

Of course, I could be wrong. But, FWIW, here is my taxonomy of the four basic schools of thought about AI, viewed in relation to Trump’s newly relaxed chip export policy, along with the reasons their views don’t make sense to me.

1. The Carefree Accelerationists. The core belief of this faction is that the faster AI advances the better, period. The most influential of the carefree accelerationists, White House AI “czar” David Sacks, helped push the new China chip policy through and also pushed for the executive order, issued this week, that authorizes the punishment of states that try to regulate AI. Sacks also helped get Persian Gulf money involved in building AI infrastructure.

Among my problems with this faction: I don’t understand how any sensible person could (1) ponder the recent impact of social media on human society and (2) still be sure that human society will gracefully absorb even more abrupt and far-reaching technological change—so sure that they think we should dial up the abruptness if at all possible!

2. The China-hawk Accelerationists. Though selling advanced chips (the Nvidia H200 in this case) to China will probably accelerate AI development, there’s a big subset of accelerationists who oppose the move. They believe that one reason America has to develop AI as fast as possible is so it can win a tech race with China (which some of them consider existential). That’s the one asterisk they add to their conviction that AI will usher in a wonderful future: *so long as we beat China in the AI race.

I have two problems with the China-hawk accelerationists: the “accelerationist” part (see above) and the “China-hawk” part (see below).

3. The AI Safety Community. People in this faction worry about one or more of the big AI risks, ranging from sci-fi-type doom (notably AI takeover) to more mundane dangers, such as a global pandemic caused by a bioweapon designed with an AI’s help. And they tend overwhelmingly to be China hawks, at least in the sense of favoring chip export restrictions and worrying about the outcome of the AI “race” with China.

A good example is Zvi Mowshowitz, a famously prolific author of a famously voluminous daily AI newsletter. This week in his newsletter he said the new Trump chip export policy would give away much of America’s AI edge in exchange for “30 pieces of silver.”

Mowshowitz began this issue of his newsletter with a passage that I think is worth dissecting: “AI is the most important thing about the future. It is vital to national security. It will be central to economic, military and strategic supremacy. This is true regardless of what other dangers and opportunities AI might present.”

I take that last sentence to be a way of affirming the consistency between being an AI safety hawk and being a hawk hawk—being devoted to preserving “economic, military and strategic supremacy.” But I don’t see the consistency Mowshowitz sees, and here’s why:

The grave dangers AI safety hawks worry about can’t be adequately addressed without extensive international cooperation—cooperation tight enough to qualify as international governance. If, for example, your nation regulates AI skillfully enough to keep a bioweapon from being built on your soil, that won’t save you from the global pandemic that originates in a laxer nation; international regulation is needed. If you’re concerned about flat-out AI takeover, the argument for international governance is even stronger, for various reasons.

And serious international cooperation, let alone true international governance, is unlikely to transpire if you prioritize winning a struggle with China for “supremacy.” (Ever try to carefully calibrate the advance of a super-powerful intelligence while depending on its rapid advance for continued “supremacy” over your rival AI superpower—even as your rival, naturally, responds in kind?) What’s more likely to transpire is dangerous destabilization and quite possibly war.

4. All the other China hawks. Arrayed along the spectrum between the AI safety community and the accelerationists are people with a range of views on the regulation of AI, but pretty much all of them are in some sense China hawks; they support the chip restrictions and accept the premise that there’s an AI “race” with China that America must win.

Advocates of continued US “supremacy” often sound as if they anticipate a day when that supremacy will be assured, but they rarely say what that world will be like. And when I ask ardent advocates of tough chip export restrictions what their imagined end game is—how the US should use the leverage an AI advantage gives it—things get fuzzy.

Here’s an end game I could get behind: Tell China we’ll relax chip restrictions (which are considerable even after Trump’s policy shift) to the extent that China helps us build a framework for international cooperation on AI. In other words: Use our leverage, while it lasts, to move the world to a place where it’s not needed.

It’s tempting to lament the fact that this sort of cultivation of international governance is basically out of the question so long as Trump is president—for three long years during which AI will reach new levels of power, for better and worse. But then you remember that, if Trump was magically replaced by a typical member of the AI safety community, we might not be much safer anyway.

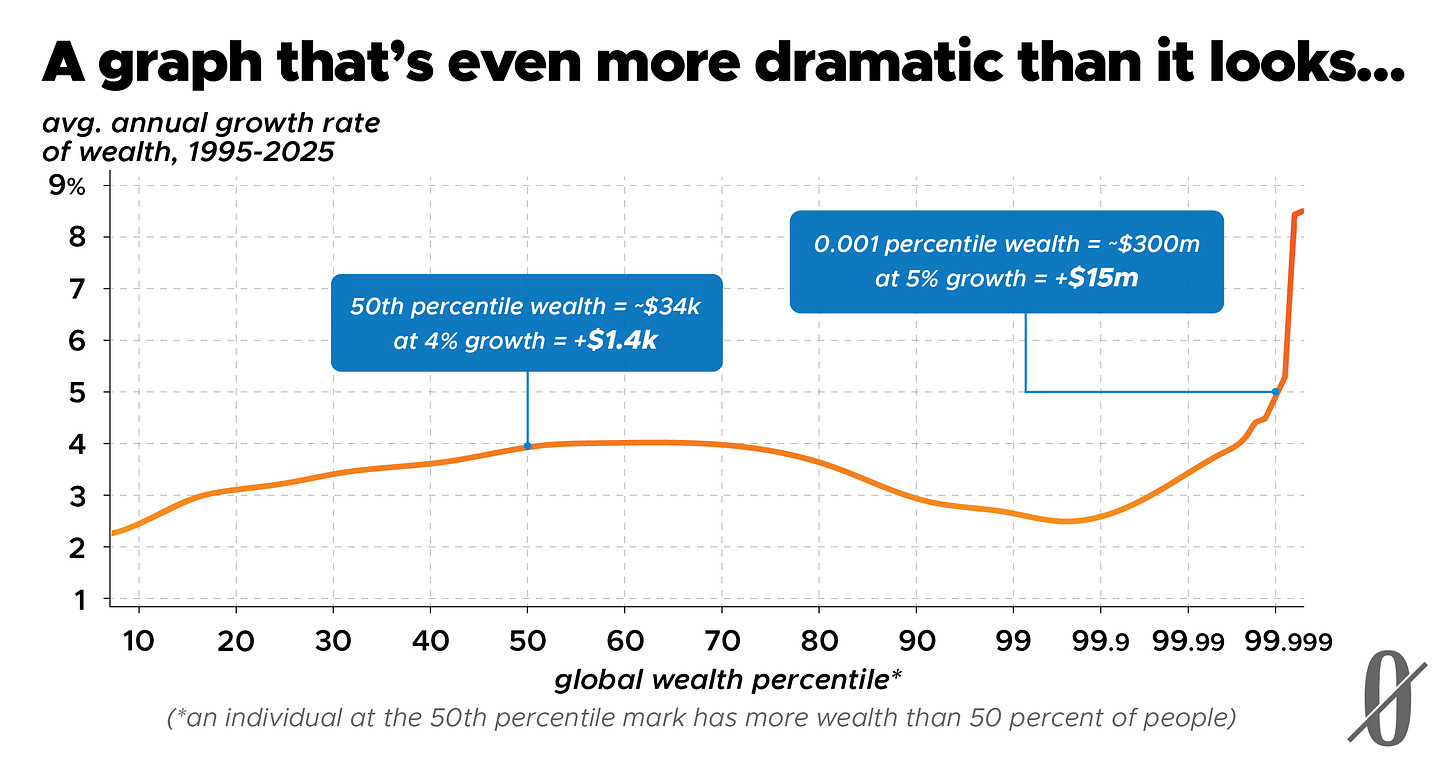

The orange line on the graph above illustrates something you might have guessed: The rich get richer. Or, to render the line’s meaning more precisely: The wealthiest part of the world’s population enjoys greater growth in wealth than the rest of the population. But note that this graph is measuring this growth in percentage terms. If instead the y axis measured the growth in absolute terms—in number of dollars, say—the roughly horizontal parts of the line would be sloping upward, and the steeply sloping part of the line at the highest wealth levels would be very, very, steeply sloping. The text in the blue boxes makes the point.

This week President Trump’s Venezuela strategy shifted from bombing small boats to seizing big ones (which, as some observers have noted, raises the question of why the US couldn’t have just seized the small ones in the first place). The seized boat was a Venezuelan tanker that, the Trump administration said, was evading US sanctions on Venezuelan oil.

Those sanctions originated during Trump’s first term, and the stated justification for them is one you could call neoconservative: They were punishment for the Venezuelan government’s undermining of democracy and human rights. This raises a question: Why does a president who purports to reject neocon foreign policy not infrequently wind up practicing it?

The standard MAGA explanation for neocon policies during Trump’s first term is that the president was manipulated by deep state holdovers from administrations past. And the standard MAGA claim is that this time things are different: Trump has staffed his administration with true America Firsters and so won’t engage in the kind of neocon regime change operations he has repeatedly denounced.

And yet… Trump named a (supposedly reformed) neocon, Marco Rubio, as secretary of state, and Rubio has been pushing Trump toward a regime change war with Venezuela.

So why aren’t more MAGA America Firsters up in arms? Why aren’t they demanding Rubio’s scalp? I explored this and other foreign policy issues—including Trump’s China chip policy, turmoil in Africa, and new fissures in the Middle East—with Derek Davison and Daniel Bessner of the American Prestige podcast, in the latest of our every-six-weeks-or-so NZN-AP crossover episodes:

After Disney announced on Thursday that it will invest $1 billion in OpenAI, Disney CEO Robert Iger said the deal would allow Disney to “thoughtfully and responsibly extend the reach of our storytelling.” The terms of the deal suggest that it will also extend the length of unemployment lines in Hollywood. The deal will mean that Sora—the OpenAI social media site where users of the company’s Sora video generation software share their creations—can feature Disney characters without OpenAI or those users getting sued. It will also mean, as the Wall Street Journal noted, that “a curated selection of videos made with Sora will be available to stream on Disney+...” My rough translation of that is: Disney will crowdsource the creation of streaming content, which it currently has to pay for, and it won’t have to pay the crowd because (presumably) Sora’s terms of service will commit users to surrender ownership of the content they post.

OpenAI’s increasing aversion to highlighting negative impacts of AI has “contributed to the departure” of at least two members of the company’s economic research team, sources told Wired. One of them, in a parting message to colleagues, “wrote that the team faced a growing tension between conducting rigorous analysis and functioning as a de facto advocacy arm for OpenAI, according to sources familiar with the situation.”

In the Transformer newsletter, Lynnete Bye says that if we want AIs to quit misbehaving in ways reminiscent of dystopian science fiction, maybe we should quit letting them read dystopian science fiction. Bye notes that large language models—during safety tests, at least—have evinced troubling behavior. Like, for example, faking alignment with the values of their overseers while being evaluated and then, once they’re no longer under evaluation, serving other values.

One theory of what’s going on, Bye says, is that AI training data includes lots of descriptions of AIs misbehaving and “the model may slip into that persona and behave accordingly.” If that’s indeed what’s going on, “one option would be to filter out all ‘AI villain data’ that discusses the expectation that powerful AI systems will be egregiously misaligned, including sci-fi stories, alignment papers, and news coverage about the possibility of misalignment.”

The title of Joel Achenbach’s deeply reported Slate piece about NASA’s space exploration plans—“Moondoggle”—captures the vibe. Achenbach doesn’t have anything against the basic idea behind NASA’s “Artemis program”—sending humans back to the moon. But he says that a) the program is a “dog’s breakfast,” drawing on “heritage hardware” and “optimized for political coalition building”; and b) NASA sees Artemis as part of a “Moon to Mars” package deal that culminates in human habitation of Mars—and nobody has a clear plan for realizing the “human habitation of Mars” part.

Achenbach recommends that we (1) recognize how enlightening (and safe and relatively cheap) unmanned exploration can be; and (2) abandon Elon Musk’s idea that we should turn Mars into a “backup drive” in case Planet Earth implodes. Spending time on Mars, Achenbach suspects, would make us “appreciate all the more the beauty and congeniality of our own planet.” Maybe, he suggests, “our fate as human beings is to save it.”

Banners and graphics by Clark McGillis.

Bob includes a good organization and analysis of the key issues in the AI policy debate. I will be forwarding it to friends who are alerted to AI’s risks, but not necessarily following the debate closely.