Which AI Titan should you root for?

Plus: Graph of the week and Quote of the week (with searing commentary)

AI acceleration is in the air.

OpenAI said on Monday that its revenue in 2025 was $20 billion—a threefold increase over the year before, which was a threefold increase over the year before that. Three days later, Dario Amodei, CEO of OpenAI rival Anthropic, told an audience in Davos that Anthropic’s revenue, though only half of OpenAI’s, had grown ten-fold in 2025—and ten-fold the year before that. Meanwhile Google, once an also-ran in the large language model race and even the subject of ridicule (remember the “woke” version of Google Gemini that gave us Black Vikings?), has gotten rave reviews for recent AI offerings and is adding users at a rate that’s rapidly expanding its market share even as the size of the market rapidly expands.

And then there’s Anthropic’s Claude Code. This code-writing agent has been the talk of the town this month—and not just if you live in a town full of computer coders; non-coders have found it to be the best “vibe coder” yet, and they’re using it to build apps without understanding the first thing about building apps. Still, the most direct accelerating effect of Claude Code—and of coding tools made by OpenAI and Google—is coming via the coders. All these coding tools, according to the people who use them in the big AI labs, have started to speed up AI progress. That may help explain why OpenAI, Anthropic, and Google have all, within the past few months, released new flagship LLMs that were clear advances over their existing LLMs—and why it seems like every day brings a new “best” along some metric of LLM performance or other. (Today’s example is a new math milestone for OpenAI’s GPT-5.2 Pro.)

Presumably the AI progress that is sped up by good coding tools will lead to better coding tools (as well as other AI tools that aid AI research)—which will further speed up AI progress, which will lead to still better tools… and so on. This positive-feedback cycle doesn’t quite qualify as the “recursive self-improvement” that AI visionaries predict—the process by which an AI creates better and better versions of itself with few or no humans in the loop. So we’re not yet at what some of these visionaries call “the singularity”—the point at which something super-amazing happens, something either amazingly good or amazingly bad, depending on whether you’re an AI booster or an AI doomer. Still, things that arrive via positive feedback cycles have a way of sneaking up on you. As a character in Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises puts it when asked how he went bankrupt: “Gradually and then suddenly.”

Even many people in AI who don’t use the term “singularity” say we’re approaching something with growing speed, some kind of threshold that will prove transformative. Most of these people call the threshold “artificial general intelligence” (AGI), and some call it something else (“powerful AI” is Amodei’s preferred term). Their exact definitions of it vary, but pretty much all of them seem to agree that somewhere in the vicinity of this threshold the impacts of AI get very big—the good ones (curing intractable diseases, for example) and the bad ones (job loss, powerful online brainwashing, the risk of various disasters with prefixes like bio- and cyber-).

Amodei thinks this threshold could come in a year or two. Demis Hassabis, head of Google’s DeepMind, thinks 5 to 10 years is more like it. But we’re already seeing hints of the challenges the threshold will pose. OpenAI said this week that its newest coding agent could give cyberattackers new power, and Anthropic has said its latest generation of LLMs could do the same for bioweapons makers. (Anthropic pondered giving this generation an unprecedentedly alarming AI Safety Level 4 rating—having given the prior generation an unprecedentedly alarming AI Safety Level 3 rating in May of last year—but then decided to stick with 3 while acknowledging that this was a close call.)

If the various risks and downsides of AI are indeed going to get bigger over the next few years, then it matters all the more which of the big makers of “frontier models” is in the lead. After all, whether the latest AI capabilities are deployed responsibly depends partly on who is deploying them. This would be true in any event, but it’s especially true when you have a president who is against meaningfully regulating AI.

There’s a second, and related, reason that the prevailing air of AI acceleration adds moment to the question of whether OpenAI, Anthropic, or Google is at the head of the pack. If indeed “threshold” isn’t too strong a word for what lies ahead, the company that gets there first could become enduringly dominant. In 2023, when Anthropic was doing a $5 billion investment round, the deck it sent to investors included this line: “We believe that companies that train the best 2025/26 models will be too far ahead for anyone to catch up in subsequent cycles.” Well, if the coming threshold is really a threshold, and Amodei is right about how soon it could get here, maybe he should change “companies” to “the company.” Maybe it will be winner take all.

So who would we want to be the winner? Anthropic, Google’s DeepMind, or OpenAI? Which would be the most responsible steward of a kind of power that has no real precedent in the history of the planet? This is too complicated a question to settle in a few paragraphs, given all the factors involved, and I’ll be revisiting it periodically in this newsletter. For now, I’ll just offer a preliminary answer to the People Magazine version of the question: Who would I most trust with the planet’s future—Amodei, Hassabis, or Sam Altman?

Well, based on this week’s evidence, especially, the winner is… Demis Hassabis.

In an appearance at Davos this week, Hassabis was asked by Emily Chang of Bloomberg to imagine that all the other big AI companies around the world were willing to “pause” the development of bigger AI models in order “to give regulation time to catch up, to give society time to adjust to some of these changes.” She asked, “Would you advocate for that?” His reply:

“I think so. I’ve been on record saying what I’d like to see happen. It was always my dream… that as we got close to this moment, this threshold moment of AGI arriving, we would maybe collaborate, you know, in a scientific way. I sometimes talk about setting up an international CERN equivalent for AI where all the best minds in the world would collaborate together and do the final steps in a very rigorous scientific way involving all of society, maybe philosophers and social scientists and economists, as well as technologists to kind of figure out what we want from this technology and how to utilize it in a way that benefits all of humanity. And I think that’s what’s at stake.”

Hassabis got an online ovation from AI Safety advocates for saying he’d be up for a pause if his competitors were game. But it’s actually a pretty easy thing to say, since no one envisions all the other players being game anytime soon. In fact, Hassabis himself added this about the prospect of an AI pause: “Unfortunately, it kind of needs international collaboration, because even if one company or even one nation or even the West decided to do that, it’s no use unless the whole world agrees, at least on some kind of minimum standards. And, you know, international cooperation is a little bit tricky at the moment. So that’s going to have to change if we want to have that kind of rigorous scientific approach to the final steps to AGI.”

When this subject came up at a different Davos event—a dialogue between Hassabis and Amodei—Amodei said roughly the same thing: Sure, it would be better for the world if we slowed the AI race down, but that’s just not realistic given the geopolitical situation.

Still, there’s a difference between Hassabis and Amodei on this score. Hassabis’s past pronouncements make it clear that institutionalized international cooperation on AI really has long been a dream of his and indeed may lie near the center of his AI ideology. Amodei has made it clear that somewhere near the center of his AI ideology lies a very different kind of goal: western hegemony over China.

In his 2024 essay Machines of Loving Grace, Amodei explained how the West could keep the most powerful AIs out of the hands of an “authoritarian bloc.” The US, he said, should lead a coalition of democracies that would restrict the authoritarians’ access to key technologies and then “use AI to achieve robust military superiority,” after which these democracies could “parlay their AI superiority into a durable advantage.” This could “lead to an ‘eternal 1991’—a world where democracies have the upper hand.” Then, Amodei says, the democratic coalition could use this stick to get these autocracies to “give up competing with democracies” unless they want to “fight a superior foe.”

That’s a pretty different vibe from the Hassabis vibe, and in my view a much less auspicious one. But I’ll give Amodei this much credit: His position seems to be sincere; he cares about the future of the world and is committed to his vision of how to safeguard it, however misguided I may consider his vision.

I suspect that this distinguishes him from Altman, the third American contender for post-AGI steward of AI. I’m not sure Altman even has much in the way of an ideology. He seems to me too committed to his corporate goals to let values get in the way. In 2024, when asked about OpenAI’s subscription-based revenue model, he said that the most commonly discussed alternative—putting ads in AI—was “uniquely unsettling to me.” Last week OpenAI announced that it will start showing ads to non-paying users of ChatGPT.

Some might say there’s a fourth American AI titan to consider: Elon Musk, an estranged co-founder of OpenAI who went on to found xAI. But, for now at least, xAI’s LLM, Grok, has little market share. Plus, Elon Musk is… well, Elon Musk.

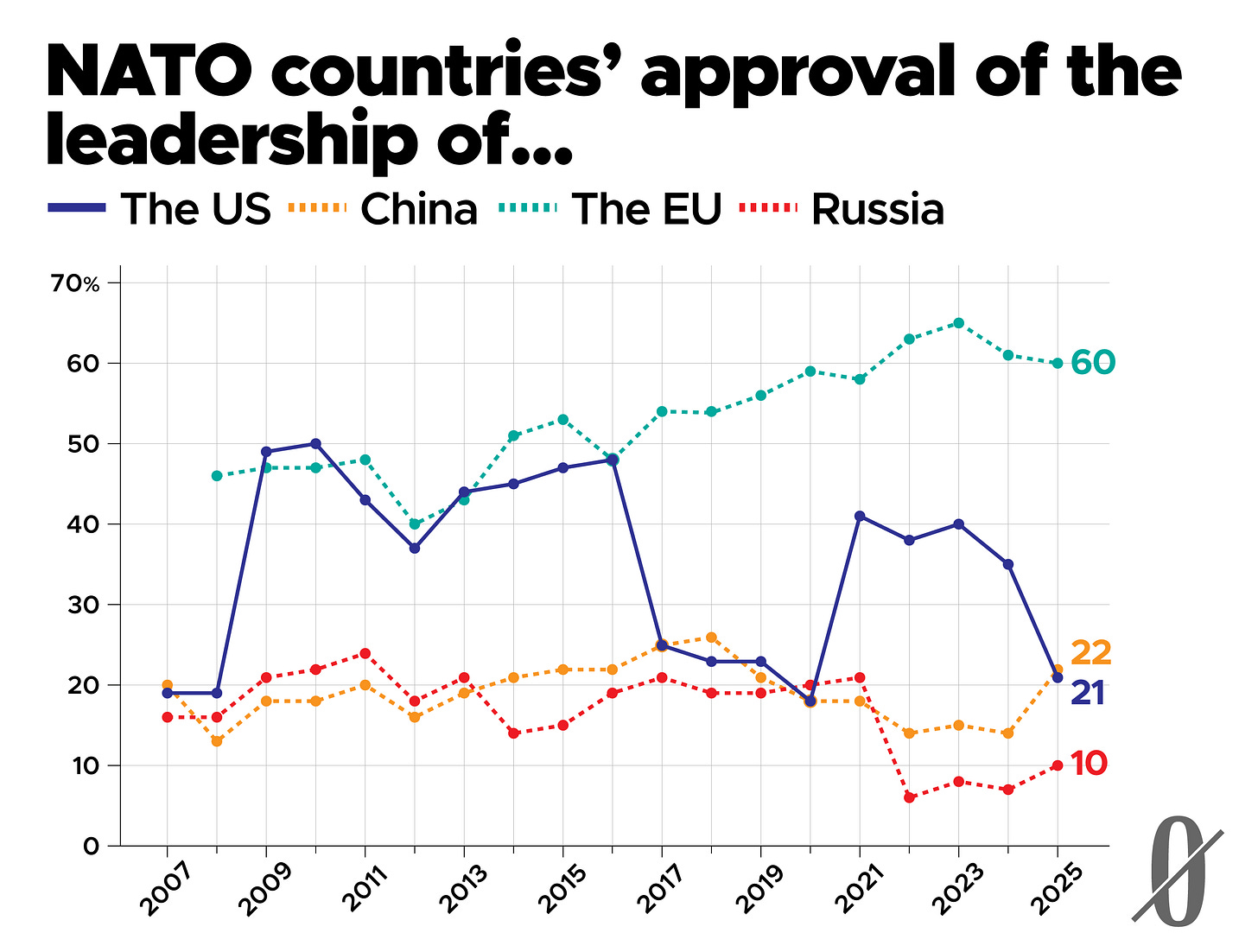

In case you’ve ever wondered how you can engineer a sudden drop in your popularity among people who live in countries that belong to NATO, the answer is now in: Either invade Ukraine or elect Donald Trump as your president.

Worthwhile Canadian Hypocrisy

This week, after President Trump renewed his vow to make Greenland part of America “the easy way or the hard way” and added a vow to impose tariffs on European nations that didn’t go along with this plan (but before Trump said that, actually, he wouldn’t take Greenland the hard way and wouldn’t be imposing those tariffs), Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney got tons of online approval for giving a speech at the World Economic Forum in Davos that was clearly aimed at Trump and featured this much-quoted passage:

For decades, countries like Canada prospered under what we called the rules-based international order. We joined its institutions, we praised its principles, we benefited from its predictability. And because of that we could pursue values-based foreign policies under its protection.

We knew the story of the international rules-based order was partially false. That the strongest would exempt themselves when convenient. That trade rules were enforced asymmetrically. And we knew that international law applied with varying rigor depending on the identity of the accused or the victim.

This fiction was useful. And American hegemony, in particular, helped provide public goods: open sea lanes, a stable financial system, collective security and support for frameworks for resolving disputes.

So, we placed the sign in the window. We participated in the rituals. And we largely avoided calling out the gaps between rhetoric and reality.

This bargain no longer works.

Dissenting from the enthusiastic mainstream applause Carney got were a few ornery leftists, such as Jeet Heer, who wrote in the Nation that “If Carney really wanted to change a global system where the strong prey on the weak, he could join nations in the Global South, such as South Africa, and the outliers in Europe, such as Ireland and Spain, in condemning the United States and Israel.”

It’s true that Carney hasn’t made a habit of condemning those two countries. Last June, after Israel launched its unprovoked attack on Iran in violation of international law, Carney said on X that Iran is a threat to regional peace and “Canada reaffirms Israel’s right to defend itself and to ensure its security.”

Maybe this is the kind of thing Carney had in mind when he admitted that “we largely avoided calling out the gaps between rhetoric and reality.”

But he may soon have an opportunity to redeem himself. As this weekend approached, there was talk of another attack on Iran, perhaps by the United States. If that happens, and Iran retaliates by firing missiles at, say, a US aircraft carrier, I’ll be checking Carney’s X account to see if Canada has reaffirmed Iran’s right to defend itself.

Banners and graphics by Clark McGillis.

As a mathematician, I use xAI's Grok regularly, as I find it vastly superior to the other models in terms of reasoning, logic etc. It could be argued that these are the key traits that must be pursued in order to reach AGI. And if reaching AGI is indeed a pivotal winner-take-all moment, then Grok's current little market share may not be a relevant factor (if the market share is even correct; many might use Grok via X – I don't know if it's in the statistics).

one important difference between hassabis and amodei is that hassabis runs deep mind, which is an alphabet subsidiary, while amodei runs anthropic, which is independent.

this does cut both ways. hassabis is at least nominally beholden to alphabet shareholders, and for things to go well in a deep mind-owned future, one has to trust not just hassabis and deep mind but also alphabet and its executives. on the other hand, while anthropic's independence and ai safety culture is presumably less likely to get co-opted by corporate influence, as a small company with less experience working with government, they may be more likely to get nationalized in a way that goes poorly.

i do think company culture below the executive level is also important, because beyond a certain size of organization the executive team only has so much influence on the workings of the company. historically anthropic has been the standout here (noting that i'm referring to regard for long-term risks from AGI here, not necessarily the geopolitical issues that you're primarily concerned with in this piece), though a friend who works there tells me that the culture has been diluted somewhat over the past few years as anthropic has become an attractive resume line for careerists.