The Trump Doctrine

The assault on Venezuela as a window on Trump’s mind. Plus: The intra-partisan AI divide; Japan’s offshoring of robot minders.

Note: Sorry about the lateness of this week’s Earthling—I was at a nearly all-consuming conference Wednesday through Friday and spent the heart of Saturday on a wifi-less airplane. I hope you find that excuse convincing, because I’m also deploying it to explain why this week’s Earthling is a bit shorter than usual—one substantial piece and a couple of leaner offerings. Tune in next week to see if my performance improves.

—Bob

“Well, I don’t think we will necessarily ask for a declaration of war. I think we are just gonna kill people who are bringing drugs into our country. Okay? We’re gonna kill them. They’re gonna be, like, dead.”

—President Trump, Oct. 23, 2025

This week, four days before the US announced it was deploying an aircraft carrier to the Caribbean, where a regime change operation against the Venezuelan government is taking shape, the Wall Street Journal ran a piece that helps explain why the operation is taking shape.

It’s been known for weeks that one reason a president supposedly opposed to neocon regime change wars is heading toward a neocon regime war is that his Secretary of State, Marco Rubio, is a neocon (whatever Rubio may have presented himself as while adapting his profile to the MAGA era and auditioning for a job in the Trump administration). What’s more, he’s a neocon who has long been more or less obsessed with ousting Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro.

What the Journal piece adds to this picture is that other influential people in Trump’s circle also have reasons to champion aggression toward Venezuela—most significantly Stephen Miller, the influential White House adviser who is a strident nationalist and harsh immigration restrictionist and is openly disdainful of the rule of law. Miller, according to the Journal’s reporting, likes the idea of using force to interdict the flow of drugs from Venezuela—the official and implausible rationale for the massive accumulation of military force near the country—but also thinks, as one source put it, that Trump’s campaign against Venezuela could “potentially enable the deportation of more immigrants who are living in the country illegally” (presumably by installing a Venezuelan regime that accepts and in some cases imprisons lots of deportees).

Meanwhile, Attorney General Pam Bondi and Chief of Staff Susie Wiles find Venezuelan regime change appealing because, like Rubio, they’re Florida Republicans, and hostility toward the Cuban and Venezuelan governments is de rigueur in that community, even if you’re not the firebreathing neocon that Rubio has traditionally been. All told, according to one source the Journal quotes, “the pressure campaign against Maduro is at the center of a ‘Venn diagram of interest’ among Trump’s top lieutenants.”

The obvious question is: What’s in it for Trump? Is he being bamboozled by advisers with their own agendas, or is there part of his agenda that overlaps with that sweet spot in the Venn diagram? The Journal piece offers an answer of sorts: Trump sees this “aggressive campaign as a foreign-policy win that could be an economic boon for the US given Venezuela’s vast reserves of oil and other natural resources.”

But this doesn’t entirely make sense. There’s a much easier way for the US to benefit from Venezuela’s oil and other natural resources: Relax the sanctions that now make it so hard for the US to benefit from them! In fact, as the Journal notes, Trump envoy Ric Grenell was months ago working on a deal under which those sanctions would be relaxed—and Maduro would agree to make economic reforms and release political prisoners. This approach, compared to Trump’s current approach, would have the added economic virtue of not increasing the federal deficit by hundreds of millions if not billions of dollars in military expenses.

No matter. Rubio opposed Grenell’s initiative and prevailed.

But, even if it’s hard to believe Trump’s approach to Venezuela is driven by a quest for an “economic boon,” might the Journal be right in saying Trump sees a “foreign policy win” in Rubio’s Venezuela policy? That question leads to the question of what Trump defines as a “foreign policy win”—a question that in turn leads to a piece published this week by the journalist Daniel Larison in his Substack newsletter Eunomia. The piece is about “the Trump Doctrine,” and it puts Larison in the long line of commentators who have tried to characterize a president’s foreign policy via an eponymous “doctrine.” The “Reagan Doctrine,” for example, was defined by the late columnist Charles Krauthammer as a willingness to go beyond the mere “containment” of communism and use proxy forces to “roll back” communism by toppling pro-Soviet regimes.

In defining the Trump Doctrine, Larison drew inspiration from Trump’s response to a question about the legality of bombing boats on grounds that the US is “at war” with the drug cartels these boats allegedly serve—the response, above, that serves as the epigraph for this piece. Larison wrote, “Trump’s statement sums up the core of his foreign policy… He is going to unleash death and destruction because he feels like it and because no one is stopping him, and he isn’t bothering with any pretense of respecting the law. The president will order US forces to commit murder without end, and he makes no secret of it. He thinks it is something to boast about.”

I think that last sentence is important. Trump sees the use of violence and intimidation abroad—so long as it doesn’t have an immediate and conspicuous downside, like significant numbers of US troops dying—as something that will elevate his stature in the eyes of most Americans. Which means he thinks it’s good foreign policy—since Trump, like many politicians, defines good policy as policy that helps him politically.

Larison continues: “Contrary to a lot of bad analysis over the years, the president is not reluctant to use force. He jumps at the chance to use it, especially when there is no chance that the target can fight back. There are many non-lethal and non-military alternatives available, but he has decided that ‘we’re gonna kill them.’ That is the real Trump ‘doctrine.’ ”

I wouldn’t call that the “real Trump doctrine” in the sense of being a crystallization of Trump’s whole foreign policy paradigm—the unifying theme of his policies toward other nations. Then again, that’s not the way the term “doctrine” has been used in this context anyway. Rather, a “doctrine” is the most distinctive and important theme that a president adds to the pre-existing US policy paradigm. The “Carter doctrine,” for example, was the idea that the US would go to war with a nation that seemed to threaten its access to Persian Gulf oil.

In that sense, I think Larison’s nominee for “Trump Doctrine” is a good one. More than any recent president, Trump feels unconstrained by national and international laws and norms. And he is unmoved by human death and suffering except when it’s framed sympathetically by someone who has his ear. So, given his belief that acting tough is good policy—which is to say, crowd pleasing policy—he will kill anyone anywhere if someone in his administration furnishes a half-credible rationale and he guesses that the near-term downside will be modest. (Remember the Suleimani assassination during his first term? No other president in living memory would have done that.)

The only other good candidate for “Trump doctrine” I can think of is, unlike Larison’s nominee, a doctrine I approve of: More than any recent president, Trump is willing to do deals with other countries regardless of their ideological character. This is a breath of fresh air compared to, for example, the Biden administration’s neoconish framing of foreign policy as a global war between democracy and autocracy, a policy that, among other downsides, pointlessly damaged relations with China.

But of course, if this laudable Trump inclination prevailed, the US wouldn’t now be gearing up for a regime change operation that Rubio has for more than a decade justified on grounds that the Venezuelan government is authoritarian and autocratic. In other words: When it comes to Venezuela, the two best candidates for “Trump doctrine”—essentially disregarding the ideological character of foreign governments and capriciously using military force regardless of legal and normative strictures—are in tension. And so far it looks like Daniel Larison’s candidate is winning.

In the Philippines, tele-operators are earning around $300 a month to steer shelf-stocking robots in convenience stores thousands of miles away, in Japan, reports the nonprofit tech-news site Rest of World. The machines work capably most of the time but bungle about 1 in 25 tasks—knocking over cans, say—and in those cases the remote robot minders, wearing VR headsets, take control (and succeed in rectifying 3 out of 4 bot blunders). The Japanese firm behind the robots says it’s monitoring these workers to create “unique ‘embodied’ teleoperation data” that will make the machines more and more autonomous. In other words: the operators, whether they realize it or not, are training themselves out of a job.

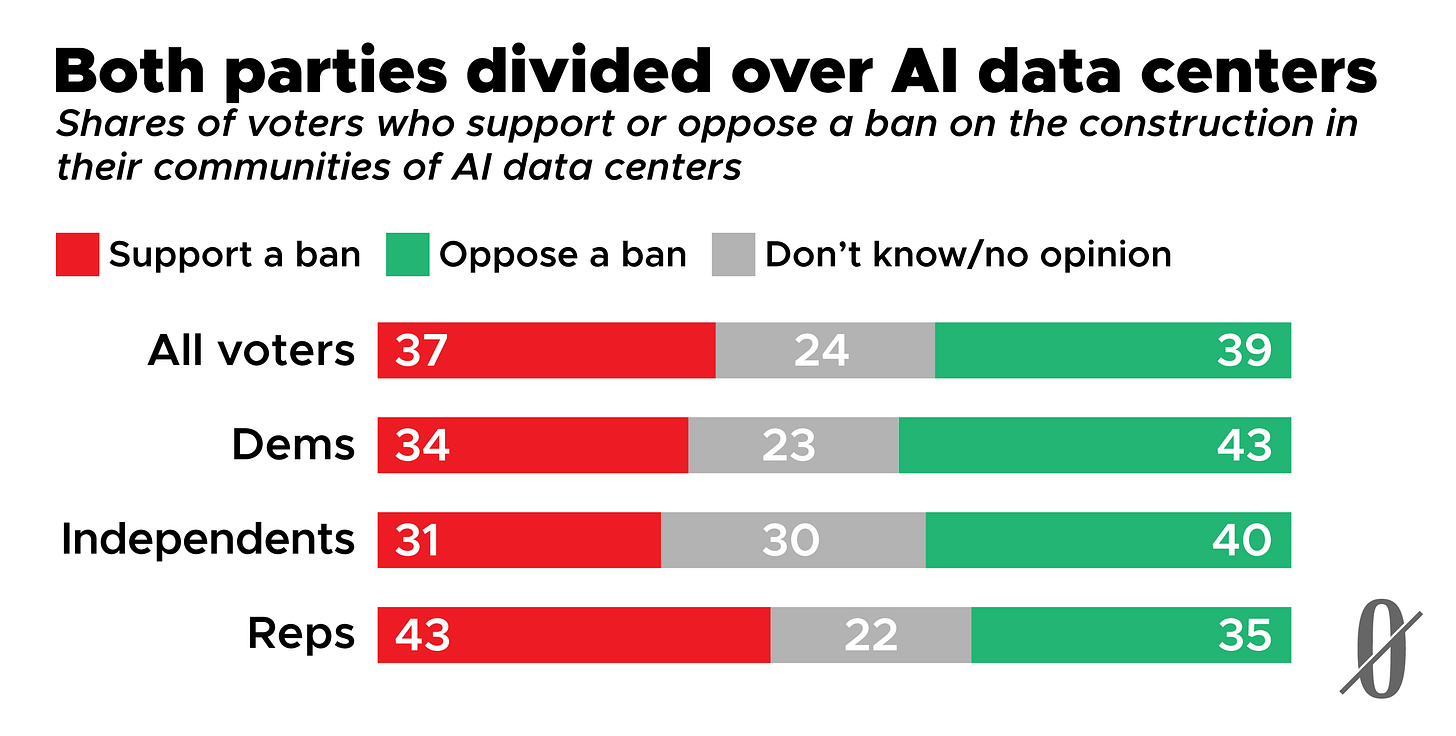

A new poll by Morning Consult suggests that the Democratic and Republican parties may face divisions over AI policy:

Of course, data centers represent only one aspect of AI’s impact. And for various reasons there is no doubt a difference between the average Republican and Democratic voter’s experience with the costs and benefits of a nearby data center. Still, data centers have become a kind of symbol of rapid AI development. And even if they hadn’t, the phrasing of this survey question—about “data centers that support AI”—would make it, for some respondents, a barometer of sentiment toward AI generally.

AI is a very fluid issue. As more people come in contact with more aspects of it, pretty much everyone will become aware of both upsides and downsides, and it’s hard to predict which of those will prevail within which constituencies. So stay tuned.

Meanwhile: Thanks to all the readers who took our three-question test to gauge AI optimism/pessimism. In next week’s issue we’ll report the results.

Banners and graphics by Clark McGillis.

Let us please not forget that Obama was the king of extrajudicial killings, even of American citizens.

As far as sentiment about AI data centers, perhaps the question should be amended to "Do you favor data centers that support AI, at the cost of doubling your utility bill?" That might elicit much different responses.

People living in states where data centers exist might compare electricity charges from last September to this September. My household used the same KWHrs each year. This year the cost was 91 cents higher each day.