Nearly a year ago, I had coffee with someone who runs a DC think tank. We talked for a while about how much turbulence President Trump had created in the course of a mere month in office, and then we talked about how much turbulence AI could create in the coming years. Near the end of our conversation, she said, “I can’t believe we’re getting Trump and AI at the same time.” My sentiments exactly.

But are my sentiments on target? Is it really clear that, just because Trump has a knack for destabilizing more or less everything, he will exacerbate the naturally destabilizing effect of AI? Isn’t there some reasonably realistic scenario in which Trump winds up exerting a stabilizing influence on the unfolding AI revolution, however ironic that might seem?

This is a particularly apt week to examine the question of whether Trump’s and AI’s turbulent tendencies are indeed fated to interact destructively—or whether, instead, there is cause for hope. I say that not because this was a particularly notable week in Trump-induced turbulence. True, he dispatched a second aircraft carrier to the Middle East, as betting markets put his chances of attacking Iran by the end of March at around 30 percent. And, true, his economic strangulation of Cuba approached an acute phase, as the island nation entered an energy crisis that is reportedly exacerbating, among other things, the death rate of children in hospitals. But for Trump, threatening to unleash chaos in the Middle East while trying to induce regime collapse in the Caribbean via the collective punishment of 11 million innocent people is baseline turmoil induction. Just another week at the office.

More notable was the week in AI-induced turmoil. Leave aside the mounting evidence of accelerating technical advance. (Yesterday, for example, Google introduced a new large language model that, on some major evaluation metrics, blew away the much-marveled-at Anthropic Claude Opus 4.6 LLM, which was released only a week earlier.) The more important advance was in awareness of the acceleration. The growing conviction of AI insiders that things are speeding up majorly—something I wrote about in NZN three weeks ago——this week reached AI outsiders en masse. As one outsider, Wall Street Journal columnist Peggy Noonan, wrote on Thursday:

“Gathering anxieties seemed to come to the fore this week. AI people told us with a new urgency that some big leap has occurred, it’s all moving faster than expected, the AI of even last summer has been far surpassed. Inventors and creators are admitting in new language that they aren’t at all certain of the ultimate impact. The story rolled out on a thousand podcasts, posts and essays.”

Noonan titled her piece: “Brace Yourself for the AI Tsunami.” I personally prefer the earthquake metaphor, but for present purposes—trying to envision a positive interaction between Trump and AI—maybe a hurricane metaphor is better. Think of Trump and AI as two hurricanes approaching each other. Since both hurricanes will spin counterclockwise (if in the northern hemisphere) or clockwise (in the southern), their winds, at the point of first contact, will be blowing in opposite directions and thus will exert a mutually subduing effect.

There. Do you feel reassured? Me neither. So let’s move to the non-metaphorical level. Is there a set of assumptions under which Trump and AI could plausibly wind up interacting in a constructive way?

Yes! In fact, this heartening scenario requires only two assumptions, creatively applied, and neither of them is entirely crazy.

Assumption number one (my favorite): that I was right when I argued in a 2023 Washington Post op-ed that the AI revolution demands “a basic reorientation of foreign policy.” Specifically: The US must “reverse the current slide toward Cold War II and draw China into an international effort to guide technological evolution responsibly.”

The basic logic here is straightforward:

Some of the biggest policy challenges that AI poses are inherently international—cases where policy at the national level alone can’t bring national security, so international coordination is necessary. To take one of the less imaginative examples: Ensuring that no US company makes AIs that help bad actors build bioweapons wouldn’t solve America’s AI-bioweapons problem. After all, a contagious lethal pathogen would probably find its way to the US regardless of which AI, in which country, abetted its creation. Lots of other big AI threats—rogue AI agents, for example—could also be threats to the US regardless of their country of origin.

So nations will need to agree on some safeguards, including stringent ones, and will need to provide enough transparency to demonstrate compliance. And China and the US—as the world’s two great AI powers, and the world’s two great powers, period—will have to be on the same page if this kind of international governance is going to happen. As New York Times columnist Ross Douthat, in the latest episode of his Interesting Times podcast, put it to China hawk Dario Amodei, CEO of Anthropic: “But isn’t it… likely that if humanity survives all this in one piece, [that] will be because the US and Beijing are just constantly sitting down, hammering out AI control deals?”

It may seem hard to imagine Trump ushering in rapprochement with China, given his history of intermittent antagonism toward the country. And envisioning him taking the next step—supporting the kind of international governance AI demands—requires even more effort, given his explicit rejection of global governance and the damage he’s done to international institutions ranging from the World Health Organization to the World Trade Organization. That’s why so much hangs on…

Assumption number two: that Trump isn’t ultimately a very ideological guy and so, given the right political circumstances, could wind up doing just about anything. Granted, he has some ideological instincts. He likes tariffs, and he doesn’t especially like immigration, and, again, he’s not wild about international governance. But none of those leanings rival in power Trump’s attraction to a higher approval rating. His unstinting support for the ICE offensive in Minneapolis—including his defense of the killing of Renee Good—was consistent with his ideological instincts, but once it proved unpopular it was no longer unstinting. This week the administration, in what the New York Times rightly called a “political retreat,” said it was winding down the Minneapolis operation. Suddenly Trump—whose whole political persona is organized around the image of a tough guy—wasn’t a tough guy. This man is nothing if not flexible.

Can we imagine a comparable 180 when it comes to international governance? Sure. This week’s burst in anxious awareness of AI’s coming impact was significant, but you can imagine any number of AI-induced calamities over the next couple of years that would produce a much bigger freakout. And if, in such circumstances, somebody proposes a policy proposal that would calm people down, Trump will be all ears. And if that somebody can convince him that this policy would give him a place in history alongside other historical figures who have found visionary solutions to big new problems, he’ll be sold on the idea (possibly even without any mention of a Nobel Peace Prize).

Besides, future sudden freakouts aside, Trump’s base already includes a sizeable contingent of AI skeptics and AI opponents. That contingent could of course shrink; many people haven’t yet interacted much with AI, and just about everyone will find something they like about it. Still, I’m guessing that the various dislocations AI brings will ensure a sizeable MAGA element that’s open to new and creative regulation.

Of course, serious AI regulation seems inconsistent with the libertarianism of the tech bros who helped put Trump in office—and inconsistent with his own longstanding anti-regulatory impulses. But here again Trump’s ideological flexibility could enter the picture productively. Those anti-regulatory impulses aren’t grounded in some deep intellectual commitment to Hayekian economics. (If Trump has even heard of a Hayek, it’s Salma, not Friedrich.) Trump is just another business hack who hates regulation when it hurts him and likes it when it helps him.

And as for the tech bros themselves: As a second term president, Trump won’t need their campaign contributions again. So long, suckers! Besides, Silicon Valley has a commercial interest in quelling AI anxieties just as Trump has a political interest. So a sufficiently scary AI calamity could warm even tech bros up to a bit of government intervention.

The need for international governance isn’t the only reason rapprochement with China matters. Given the magnitude and breadth of AI’s coming impact—on jobs, parenting, politics, etc., to say nothing of extreme doomer scenarios—it would be nice to slow AI advance down a bit, so we’d have more time to shape the technology and adapt to it. But if you propose a policy that would—even as a byproduct—slow things down just a smidgen (a tax on data centers, say, or a ban on particularly toxic ways of powering them, such as the noxious gas turbines Elon Musk built in Tennessee), you are met with a reflexive refrain from AI companies and their lobbyists: Slowing American AI progress down would imperil our lead over China and thus imperil our nation!

One of Trump’s ideological leanings could actually come in handy here. Though Marco Rubio and others have managed to inject an unhealthy dose of neocon moralizing into Trump’s foreign policy (along with an unhealthy attraction to neocon regime changing), Trump’s intuitive foreign policy mode is realism. Not a sophisticated or refined realism (and certainly not a progressive realism), but at least a realism that liberates him from the Manichaean autocracy-vs-democracy framing that made it so hard for Biden to constructively interact with China. More specifically, Trump’s realism liberates him from something that’s central to the world view of Dario Amodei and many other China hawks: their belief—almost wholly devoid of supporting evidence—that China wants to impose its system of government on America.

Maybe calling Trump a “realist” gives him too much credit for philosophical reflection. So here’s another way to put it: For all the talk about Trump’s zero-sum view of the world—talk that is in many ways on target—he has what you have to have in the business world unless you want to be an abject failure: a consistent willingness to play non-zero-sum games to win-win outcomes.

In other words, Trump is in principle willing to do a deal with anyone. And if we don’t do any AI policy deals with China over the next three years, I think both we and China, along with the rest of the world, will be in deep trouble.

So there’s my hopeful scenario. Unfortunately, it does include an “AI calamity.” But calamities can be profoundly alarming without being massively lethal. They can point to the possibility of something much bigger and worse without being all that bad. As long we’re searching for hope, and dreaming big dreams, let’s make that kind of calamity assumption number three.

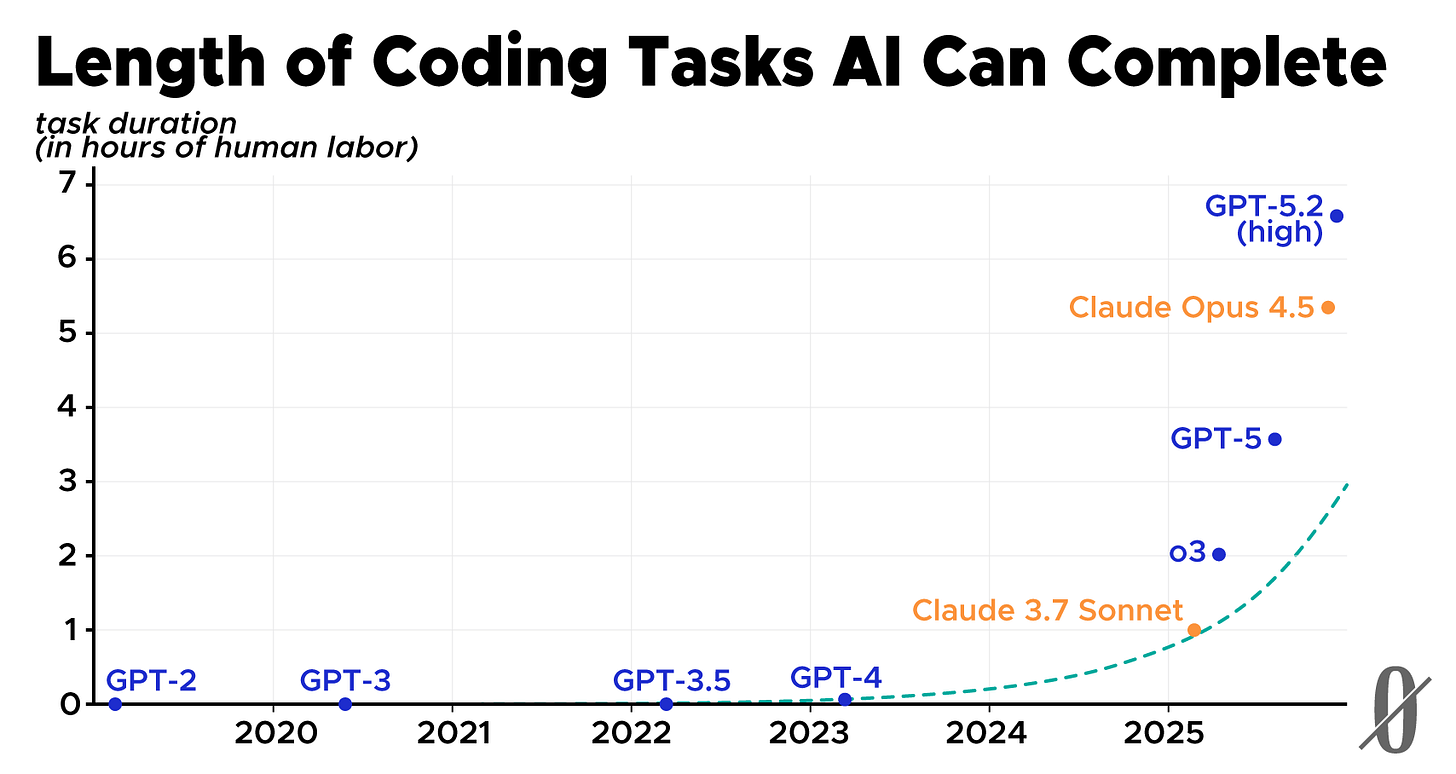

The dashed curve is the curve that was fit to the data that existed as of the spring of last year. It implied that the “doubling time” of task duration was every seven months. In other words: If the LLM that turned in the best coding performance at a given point in time could do a task that required a human programmer an hour to do—as was (roughly) the case with Claude 3.7 Sonnet at the time—then in seven months there would be an LLM that could do work it would take a human two hours to do. And so on: four hours after another seven months. But, as you can see, it turned out that the subsequent doubling times were even shorter than seven months. So a pace of AI advance that was thought to be exponential a year ago seems to be—for the time being, at least—even more dramatically exponential than was thought a year ago. (Note: Successfully performing a task is defined as performing it successfully 50 percent of the time. METR also publishes data using an 80 percent success threshold. But that graph has roughly the same shape as this one, though the task durations are of course shorter.)

Banners and graphics by Clark McGillis.

Bob’s logic here is sound, not only generally but specifically with regard to the sine qua non of international cooperation for mitigating an abundance of shared threats we face. Although I confess to having doubts, it’s pretty churlish to be dismissive about China or any other nation putting much faith in the longevity of any position Trump takes on anything (I mean, “you got a better idea buddy?”).